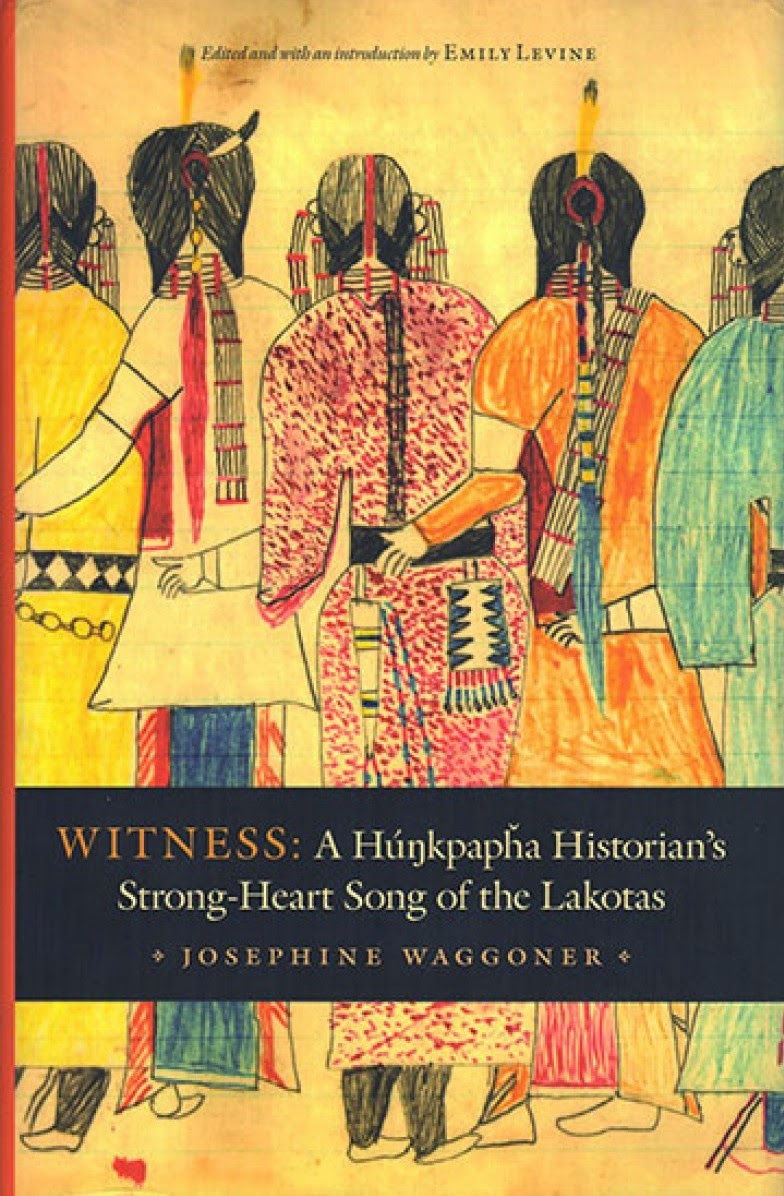

"The little brave who visited the grave of a medicine woman, with several other boys," appears in Marie McLaughlin's "Myths And Legends Of The Sioux."

Mischievous Boy Pranks Others

Mischievous Boy Pranks Others

Stunt Spreads To Village, Causes Fear

By Marie L. McLaughlin

"A Little Brave And The Medicine Woman" comes from Marie L. McLaughlin’s “Myths And Legends Of The Sioux.” It is retold here with minor edits.

A village of Indians[1] moved out of winter camp and pitched their tents[2] in a circle on high land overlooking a lake. A little way down the declivity was a grave. Chokecherry[3] bushes had grown up, hiding the grave from view. But as the ground had sunk somewhat, the grave was marked by a slight hollow.

One of the men going out to hunt took a short cut through the chokecherry bushes. As he pushed them aside he saw the hollow grave, but thought it was a washout made by the rains. As he essayed to step over it, to his great surprise he stumbled and fell. Made curious by this mishap, he drew back and tried again, but again he fell. When he came back to the village[4] he told the old men what had happened to him. They remembered then that a long time before there had been buried there a medicine woman.[5] Doubtless it was her medicine that made the hunter stumble.

Chokecherries. The fruit is ready to pick in late July/early August.

Chokecherries. The fruit is ready to pick in late July/early August.

The story of the hunter’s adventure spread through the camp and made many curious to see the grave. Among others were six little boys who were, however, rather timid, for they were in great awe of the dead medicine woman. But they had a little playmate named Brave,[6] a mischievous little rogue, whose hair was always unkempt and tossed about and who was never quiet for a moment.

“Let us ask Brave to with us,” they said, and they went in a body to see him.

“All right,” said Brave, “I will go with you. But I have something to do first. You go on around the hill that way, and I will hasten around this way, and meet you a little later near the grave.”

So, the little boys went on as bidden until they came to a place near the grave. There they halted.

“Where is Brave?” they asked.

Now Brave, full of mischief, had thought to play a jest on his little friends. As soon as they were well out of sight he had sped around the hill to the shore of the lake and sticking his hands in the mud had rubbed it over his face, plastered it in his hair, and soiled his hands until he looked like a newly risen corpse with the flesh rotting from his bones. He then went and lay down in the grave and awaited the boys.

When the little boys came they were more timid than ever when they did not find Brave, but they feared to go back to the village without seeing the grave, for fear the old men would call them cowards.

So they slowly approached the grave and one of them timidly called out, “Please, grandmother, we won’t disturb your grave. We only want to see where you lie. Don’t be angry.”

At once a thin quavering voice, like an old woman’s, called out, “Háŋ, háŋ, tȟakóža, héčhetuya! [Yes, yes, grandson, do so!]”

The boys were frightened out of their senses believing the old woman had come to life.

“Oh, grandmother,” they gasped, “Don’t hurt us. Please don’t. We’ll go.”

Just then Brave raised his muddy face and hands up through the chokecherry bushes. With the mud dripping from his features he looked like a witch just raised from the grave. The boys screamed outright. One fainted. The rest ran yelling up the hill to the village, where each broke at once for his mother’s thípi.

As all the thípi in a Dakȟóta encampment face theh center, the boys were in plain view when they came tearing into camp. Hearing the screaming, every woman in camp ran to her thiyópa[7] to see that had happened. Just then, Brave, as badly scared as the rest, came rushing in after them, his hair on end as covered with mud and crying out, forgetful of his appearance, “It’s me! It’s me!”

The women yelped and bolted in terror from the village. Brave dashed into his mother’s thípi, scaring her out of her wits. Dropping pots and kettles, she tumbled out of the thípi to run screaming with the rest. Nor would a single villager come near poor Brave until he had gone down to the lake and washed himself.

[1] Marie McLaughlin’s maternal grandmother was Mdewákhanthunwaŋ (Dwellers At The Sacred/Spirit Lake). Marie married Major James McLaughlin. She lived at Spirit Lake Agency (Devil’s Lake Agency) for ten years before moving with her husband to Standing Rock. In her book, “Legends Of The Sioux,” McLaughlin frequently uses “Sioux” and “Indian” interchangeably with Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires) and Dakȟótá or Lakȟótá (Allied; Friends).

[4] Wičhóthi: Village, camp, or encampment.

[5] The original text includes, “…or conjurer.”

[6] Ohítika: Brave.

[7] Thípi door.

%2C_a_Hunkpapa_Sioux%2C_1885_-_NARA_-_530896.jpg)