1798: Wiya ka tota an apicilo wapi.

Wiyáka tȟotȟó uŋ akíčilowaŋpi (Lit. Feathers blue-blue to-use-something singing-praise-they). They sang praises using very blue feathers.

It was agreed to among the people that any one of the tribe who was seen wearing the blue feathers should be an example to others in virtue and goodness, and should be esteemed by all as a guardian of the "nation." Four men at that time were set apart with the blue feathers.

By an old ceremony men were set apart as “Atéyapi” (Fathers) and women as "Ináyapi" (mothers). By this ceremony these people were chosen as leaders in the tribe, and their admonitions were heeded.

Sometimes a small child was raised to this class because of a portent at his or her birth that indicated his or her superior wisdom. Grown persons were raised to this class on account of some distinguished service to the tribe, as well as for manifest wisdom and foresight in affairs. Those raised to this class while they were babes are said to have been generally the most satisfactory administrators of justice. Such children received careful training both from those previously raised to this class and also from their grandmothers.

They were taught to admonish with discretion and with gentleness, to honor and respect each and every one of every age and themselves; to be kind to dogs and all animals. If one of this class proved unworthy, one was not deposed, but from that time on, or until one had purged oneself of old offenses and adopted better manners one had small influence in the council-meetings, yet the people still respected him or her.

As men were gifted with blue feathers to designate their worthiness, women were gifted with blue glass pendants they wore proudly upon their forehead, though this practice has long since faded.

Kȟaŋpéska Imánipi Wiŋ (Walking On The Shell Woman), a wife of Matȟó Watȟákpe (Charging Bear; John Grass), was among the last Lakȟóta women to have possessed one of what they called Maȟpíya Tȟó, or a Blue Cloud Stone. The stone was actually a flat blue polished piece of glass, possibly volcanic, which was melted and poured into a sand or clay mold. The stone was made by a woman of virtue, and only one was given a year. When it was worn, the woman was held in high esteem by all as good and honorable, a role model for all women.[1]

1799: Iaske wasicu tako mako el hi.

Čhaské wašíču tokhíya makȟó el hi (First-born-son takes-the-fat therefore country there came). A white man [they knew as] Čhaské came to their country.

A white man they called Čhaské came to live permanently among them for the sole purpose of trade. Previously, traders had come and gone after a short stay.

The Lakȟóta people have birth order names they call their children by, though the tradition of doing so is rarely practiced today.

Birth Order Male Female

First Čhaské Witȟókapȟa/Winúŋna

Second Hepȟáŋ Hapȟáŋ

Third Hepí Hepíštana

Fourth Čhatáŋ Waŋská

Sixth Hakáta Hakáta

The fifth born son is called Haké or Hakéla, which is sometimes used to address the last born son. The seventh born son/daughter is called Čhekpá (Navel).

Howard suggests an additional translation to this year’s entry: Iyéska wašíču tokhíya makȟó el hi (Clear-talker takes-the-fat therefore country there came), or, “A white translator came to their country.”[4]

1800: Capo ati wan miniyawe yapi.

Čhápa otí waŋ mníyawe yápi (Beaver dwelling there water-drawing go-they). [It was so cold] they drew water from beaver holes [in the ice].

This was an exceptionally dry summer. Tȟatíye Tópa (the Four Winds) drank up the streams. Women lay in distress in their lodges on account of the heat. They believed Wí (the Sun) was angry with the people over an unexplained misdeed, and so withered the grass and foliage.

The birds went to the great rivers far away, and sat in the thicket mum. The flowers were all gone. The buffalo went away. A harsh winter followed, and it was so cold that the water was sometimes drawn from beaver holes.

1801: Tahi an akicilo wapi.

Theȟí uŋ akíčilowanpi (Difficult-times of sang-with-each-other-they). They sang together during a difficult period.

At this meeting the horsetail was adopted as an insignia, or badge, for a “leader.” The horse had become important to the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ (Seven Council Fires; Great Sioux Nation) though only a portion of them had horses as yet. The horse was regarded as a sacred animal.

1802: Sir gugu lo awicakilipi.

Šúŋg’ğuğú ló, áwičaglipi (Horse-curly-hair declarative, returned-with-they). They returned with curly-haired horses.

The Huŋkphápȟa, while at war with the Crow, took some curly-haired horses from them. This battle occurred southeast of Ȟesápa (the Black Hills). A favorite hunting and camping spot located in this locale is Pté Tȟathíyopa (Buffalo Gap, SD).[5]

A first encounter of the horse can be found in the Drifting Goose Winter Count, an Iháŋkthuŋwaŋna record. In this account, 1692 is remembered as “Šuŋgnúŋi óta kiŋ,” or the year they saw many wild horses.[6]

The American Horse Winter Count recalls a conflict at this time involving the Oglála, Sičáŋğu, Mnikȟówožu, Itázipčho, and Šahíyela (Cheyenne) in a united campaign against the Kȟaŋğí (the Crow).[7]

The earliest account of a horse stealing raid can be found in the Brown Hat Winter Count (Oglála), in which 1708 is recalled as the year they stole horses from the Omaha.[8]

1803: Saki mazo awicakilipi.

Šaké máza áwičaglipi (Hoof iron returned-with-they). They returned with iron-shod horses.

The Huŋkphápȟa captured some shod horses from the Crow, and concluded that the Crow were somehow in alliance with white men. This was the first time they had seen shoes on horses, though they were aware white men’s horses wore them, and some horses of the white men were trained to strike an enemy with these iron implements.

1804: Kangi wicasa 8 wicaktipi.

Kȟaŋği wičáša šaglóğan wičháktepi (Crow man/men eight killed-they). A Crow war-party came and killed eight of them.

Eight Lakȟóta were killed by the Crow in a running battle. This occurred near Ȟesápa. Ȟesápa was contested territory between the Crow, Shoshone, the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and the Thítȟuŋwaŋ (Teton). Though the native people may have contested over Ȟesápa, but the hills were sacred to all.

1805: Nam wicakogipapi.

Núm wičhá kȟokípȟapi (Two men were-afraid-of-they). Two men [Crow] attacked the Lakȟóta camp.

The battle was long and well fought. The Crow had ridden double on a horse, which proved to put them at a terrible disadvantage; the Lakȟóta won out.

Kevin Locke (Standing Rock) phrases the concept for riding double upon a horse as “Núm akáŋ yaŋkápi.”[9]

1806: Akile luto an wan kitipi.

Ógle Lúta uŋ waŋ ktépi (Shirt Red a the killed-they). They killed a man wearing a red shirt.

In a battle with the Crow, a Huŋkphápȟa leader called Red Shirt was slain. He was considered very brave because at one point in the fight he had bravely recovered the body of a fallen Lakȟóta warrior.

1807: Fu we yo wan ktepi.

Tuŋwéya waŋ ktépi (Scout the killed-they). They killed a scout.

A Huŋkphápȟa leader, whom they called Scout, was killed by the Crow.

The Lakȟóta scout/s were carefully selected for either the hunt or for war. They should have the essential qualities of courage, having a good sense or wariness, truthfulness and having a good sense of the landscape. No more than two are sent in the same direction. By the latter half of the nineteenth century, scouts carried with them a small mirror and a field glass. Upon sight of his thiyóšpaye (a division of a tribe; extended family) he flashed his mirror if sunlight permitted, or howled like a wolf. If there were no immediate danger (i.e. enemy) the scout told his story in four parts to the Itȟáŋčhaŋ (leader; headman) or blotáhuŋka (war-party leader). If the threat were immediate, the scout quickly shared his intelligence.

The Plains Indian sign for scout is the same for wolf: hold the right hand, palm out, near one’s right shoulder, first and second fingers extended, remaining fingers and thumb closed, followed by a movement of this hand forward and slightly upward.[10]

1808: Pahato i wan ktepi.

Paháta í waŋ ktépi (To-the-hill on-account-of certain killed-they). They killed a man who went to the hill [to scout].

The Huŋkphápȟa sent a scout to find where the buffalo were as they were nearly out of meat. The Crow killed him.

1809: Taka suki ku woahiyu wega.

Tȟáŋka šúŋg’ičú wóečhuŋ wéhaŋ (Big horse-take event last-spring). [They had] a big horse-stealing raid last spring.

The Huŋkphápȟa crossed the Mníšoše (Water-Astir; Missouri River) and captured a large number of stray horses on the east bank. This gave them a better supply of horses than they ever had before. They say this crossing was made at a place a few days travel north of present-day Pierre, S.D. Perhaps this location is Šiná Tȟó Wakpána (Blue Blanket Creek), near present-day Mobridge, S.D.

1810: Wicogogotaka.

Wičáȟaŋȟaŋ tȟáŋka (Smallpox big). Epidemic of smallpox.

Smallpox struck them in winter causing a great loss of life.

The earliest pictographic record of their encounter with smallpox is seen in the 1735-1736 winter of the Brown Hat Winter Count which is remembered as “Used them up with belly ache winter.” In this account, about fifty people died from an eruptive disease which also caused pain in the bowels. The pictograph depicts eruptions on a single figure indicating sores on the body and pain in the stomach.[11]

1811: Capa cigalo ti ile.

Čhápa Čík’ala thí ilé (Beaver Little lodge on-fire). Little Beaver’s cabin caught fire.

A white man came to live with them. He built a small log house. He was a small man and was inclined to stay in his house a good deal, so they named him Little Beaver. The Brown Hat Winter Count says that this man was an English trader.[12]

1812: 8 ahi wicaktipi.

Šaglóğaŋ ahí wičátkepi (eight came killed-they). They came and killed eight.

The Huŋkphápȟa were camping along the east side of Ȟesápa. The Crow attacked them and were driven back, however they killed eight Lakȟóta. The Huŋkphápȟa beat and killed one Crow who was left behind in the fight. According to Swift Dog, the Crow war party consisted of ten warriors of whom the Huŋkphápȟa killed eight.[13]

1813: Mato cigalo ahikitipi kin.

Matȟó Čík’ala ahí ktépi (Bear Little came killed-they). [The enemy] came and killed Little Bear.

The Lakȟóta fought with the Crow. Little Bear, a leader of the Huŋkphápȟa band of Lakȟóta, was killed.

Rev. Aaron Beede questioned the Thítȟuŋwaŋ to some great depth about the War of 1812 which was then being fought in Wisconsin and beyond. In fact, they had known of the war and had believed that all Indians should keep out of it entirely until “the Whitemen [sic] had eaten up each other." They hoped an opportunity would then open and then they would have seizes the chance to regain territory as far east and south as possible. To Beede’s surprise, he discovered that this was discussed in great detail among the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ.[14]

As many as 700 Isáŋyathi (Santee; Eastern Sioux or Dakota) and Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna (Yanktonai) joined the English under the British Indian Trade Agent Col. Robert Dickson, whose wife was a Waȟpéthuŋwaŋ Dakȟóta named Ištá Tȟó Wiŋ (Blue Eyes Woman).

Dickson’s father-in-law was Wakíŋyaŋ Lúta (Red Thunder); his brother-in-law was Waná’átA (The Charger; Waneta). Waná’átA actively recruited among the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ and pursued conflict against the encroaching Americans. He rallied the English and Dakȟóta alike at Battle of Sandusky in Ohio, which was where he received the name Waná’átA, after he survived being shot nine times. He later met King George IV and President Van Buren.[15]

1814: Wito Pahato an wan ko gugapi.

Wítáya pȟeȟáŋ tȟó úŋ waŋ kaȟúğapi (Gathered-together Head Blue use by-means-of smashed-into-they). At a gathering they [he] split the skull of Blue Head [a Crow].

An enemy, whose forehead was painted blue, came to the Lakȟóta camp on pretense of visiting a friend or relative among them. He was slain by a strike in the head with a buffalo bone. This same year is recorded in the Brown Hat Winter Count as “Smashed a Kiowa’s head in winter,” and depicts a tomahawk on top of a Kiowa’s head.[16]Lone Dog, an Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna, says that this was an Arapaho whose head was cleft.[17]

James Howard transcribed the Lakȟóta text as: Wítapaha tȟó úŋ waŋ kaȟúğapi (Lit. Kiowa blue wearing a they-clubbed-him-on-the-skull), which translates freely as, “They smashed a blue-wearing Kiowa’s head.”[18]The Lakȟóta word for Kiowa (also “Osage” according to Rev. Buechel) is: Wítapahatu.[19]

The pictograph High Dog rendered clearly depicts a Crow with a blue forehead.

1815: Wamanu wan cehupa wawegopi.

Wamánuŋ waŋ čhehúpa wayúȟlokApi (Thief in-the-act-of jaw bored they). They bored the jaw of a thief.

A Lakȟóta stole a horse from another Lakȟóta, and was punished by having his jaw bored with an awl so that the mark would always be a visible brand upon him. They say this was the first theft ever known committed by a Lakȟóta against another Lakȟóta. The thief got the idea after hearing about a powerful white man on the frontier who would steal horses from other white men.

1816: Nampa wakte akili.

Núŋpa wakté aglí (Two to-have-done-killing-in-battle return [in-triumph]). A warrior returned victorious from battle with two war honors.

According to Beede’s informants, this year marks an occasion in which the Lakȟóta were engaged in one particular battle against the Crow. The Lakȟóta war-party is said to have used hoops with horsetails affixed to them which they used to signal one another. Beede suggests that the Lakȟóta were badly beaten in this conflict and that a new interpretation of this year’s story was given to the next generation to cover up this loss.

The waktégli is still remembered and practiced on Standing Rock today. In particular, this event is held to commemorate the Little Bighorn fight, as much to celebrate the last great victory against invading US military as to remember the price of that victory. Beede’s conjecture that the Lakȟóta were badly beaten is not true. An interpretation of the text and imagery suggests that a war party went and fought against the Crow, only one returned, but he returned victorious against the Crow, and recounted the sacrifices of his fellows against the enemy. The sole survivor of the war party returned with only his two war honors, scalps affixed to hoops (not horse tails).

Perhaps Beede’s informants chose only to give the barest information about the waktégli, which left an open interpretation of the event for Beede.

1817: Hico ti taka awakicago.

Héčhe, thí tȟáŋka awákičağa (In-that-way, lodge big to-make-things-on-behalf-of-someone). In the traditional manner, [they] held a memorial give-away which included the gift of a lodge.

Buffalo Bull’s son died. His name was Buzz. Buzz’ pipe was kept and wrapped in a white bison skin for one year. When a year had passed, his family gave away his belongings.

Beede’s informants, again, seemed reluctant to share little beyond the fact that Buzz’ soul was kept for a year and then released. A memorial celebration, a feed and a give-away, was held a year later. This practice, or rite, is still carried by many of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ today.

1818: Maka wablu wanitipi.

Makȟá woblú waníthipi (earth wind-blowing-fine-particles-of wintercamp). A dust storm struck their winter camp.

There was a great windy dust storm which blew the winter camp to pieces. A dusty storm in winter would seem to indicate a dry winter with little or no snow. Howard’s narrative says that many people starved this winter.

1819: Gasepih ian bulu an tekaga.

Čhozé čhaŋpúpuŋ uŋ thikáğa (Čhozé wood-rotten there to-build-a-house). Čhozé, a trapper/trader, built a cabin using rotten wood.

Beede’s notes reveal little more, other than replacing “Čhozé” with “Joseph.” Other winter counts with Lakȟóta text refer to the trader’s name as “Čhozé.”

There were two Josephs at the time, both employed by the American Fur Company, who might be the Joseph remembered here: Joseph Neumanville (a clerk) on the Grand River, and Joseph Schindler (an assistant), also assigned to the Grand River. It could easily be another “Joseph” whom this entry could be referring.[20]

Garrick Mallery asserts that this trader was the French trader Joseph La Framboise.[21]

1820: Wi ihablo iyawaci kin.

Wí iháŋbla iyé wačhí kiŋ (Sun dream that-one dance the). Someone dreamed about the sundance that time.

Beede writes, “The Sioux in this summer celebrated for the first time in their history the sundance. They had known of it before, but had never used it.” Beede’s informants tell him that medicine men of great repute at that time had persuaded the Lakȟóta to use this sacred dance which would give them power to resist the threatened inroads of the white men, and so they adopted it as part of their customs.

Beede’s informants tell him that from that time on the medicine men replaced the Wósnakağápi (they who make sacrifices), the traditional priests.

It may be an indication of the times that Beede writes from, the Christianized and civilized post-reservation era, or that his informants didn’t wish to share the fact that there are different kinds of medicine men and women. Many of the traditional practices went quietly underground and stayed quiet because they were made illegal. It wasn’t until the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 that traditional practices were allowed to be practiced in the open without legal consequence.

The earliest pictographic record of the sundance ceremony is remembered in the Drifting Goose Winter Count in 1713, but this does not mean that this is the first time they performed the ceremony.[22]

1821: Wicagipi wan hatu hiyaye.

Wičáȟpi waŋ hotȟúŋ hiyáye (Star the cry-out-characteristically-of-a-species to-come-and-pass-by). A star cried out as it passed.

Beede’s informants tell him that a star (he supposes that perhaps it could also have been a comet) fell while it was reverberating in the air. The location is unknown.

The meteor likely never actually struck the ground. The sound was probably produced in the wake of its passage across the sky, and it burned up.

The Drifting Goose Winter Count recalls a similar event in 1741, as a buzzing or humming heard throughout the land. James Howard suggests that the event was a diurnally occurring bolide (an exploding meteor), which, when entering the atmosphere, produces a sonic boom.[23]

The Brown Hat Winter Count also demarcates this year’s event as “Star passed by with a loud noise winter,” and notes, too, that this is the first time that whiskey was furnished to them. Many died from excessive use of this hard liquor.[24]

1822: Sunko wan a gi cuwita ta.

Šúŋka Wanáği čhuwíta t’A (Dog Spirit to-be-cold died). Spirit Dog froze to death.

A leader named Ghost Dog went out hunting and froze to death. Frank Zahn (Standing Rock), one of Howard’s informants, added that Ghost Dog was the son of Makȟá Ȟóta (Gray Earth).[25]

1823: Wahu wapaseco ir api.

Wahúwapa šéča ȟápi (Ear-of-corn dried to-bury-they). They cached parched ears of corn.

The Lakȟóta went to war with the Crow, and some white men stole their corn while they were away. Beede’s informants tell him that the Húŋphapȟa had adopted the Miwátani (Mandan) practice of agriculture, meaning that they grew corn, squash, and beans.

1823 also marks the first U.S. military campaign against a Plains Indian tribe, in this case, the Arikara. The Arikara had been killing white men, specifically men of the American Fur Company, after they received word of the death of one of their chiefs who was selected to go east to meet President Jefferson. He died out east, and when word of his death eventually came to the Arikara, they suspected treachery.[26]

Subsequently, Col. Leavenworth was dispatched up the Missouri River in a punitive campaign against the Arikara. About 700-750 of the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ fought under Leavenworth’s command in this Missouri Legion. At the end of the campaign, when the Arikara were utterly defeated and chased out of their villages, their fields of corn were seized by the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ for their use. Many other winter counts recall this fight with the Arikara.[27]

1824: Pte wan sayapi.

Pté waŋ sayápi (Bison-cow creamy-white-painted-they). They painted a female bison horn creamy white [in ceremony].

Beede’s informants tell him of a ceremony in which they anointed a buffalo horn with clay and hung it near the camp so as to make the buffalo come. The clay used was the same as that with which was applied to the breastbones of the scouts as they were about to go into the Little Bighorn fight.

1825: Mini wicata.

Mní wičhat’Á (Water them-died). Many had died by drowning.

They were camping on the bottomlands of the Mníšoše that spring when an unprecedented rise of water quickly drowned over one half of the people. They say that this happened on the east bank of the river, opposite of the mouth of the Cannonball River. The Dakȟóta call this place Étu Pȟá Šuŋg t’Á (Lit. Place Head Horse Dead; Dead Horse Head Point) because, following the flood, the shore was lined with dead horse heads. They had corralled their horses for the night and nearly all were drowned but for a few.

Howard’s interpretation of this event mentions that over one-half of the people drowned.[28]

1826: Magalo waktipili.

Mağála waktéglipi (Goose [familiar suffix] to-have-done-killing-in-battle-return-they). Little Goose [and his war party] returned from battle with war honors.

Beede’s translation says that it was a man named “Corn Stalk,” a famous Lakȟóta chief who went to war against the Crow and returned with scalps. The Lakȟóta text clearly says “Little Goose,” and not “Corn Stalk.”

High Dog, in fact, depicted a man with a name glyph of Corn Stalk. The figure is also depicted holding a scalp stick that is similar to other entries regarding the waktégli (the victorious return from battle, having killed the enemy).

1827: Wasima Piso ahampi.

WašmÁ psóhaŋpi (Deep-snow snowshoes). The snow was so deep that they used snowshoes.

Beede writes that this is the “first time they used snowshoes.” Howard concurs. Likely, this is the first time that Beede and Howard have seen the Lakȟóta reference snowshoes; the use of snowshoes was not unknown. They were hunting near Ȟesápa.

1828: Mato Paha el wanitipi.

Matȟó Pahá él waníthipi (Bear Butte at winter-camp-they). They established winter camp at Bear Butte.

Ȟesápa, or the Black Hills, is the very heartland of the Lakȟóta people.

1829: Wata sakiyapi.

Watásakiyapi (Wa-tȟasáka-ya-pi). ([Bison] meat frozen going-there-they). They came across frozen bison meat.

They came across a man, shot and frozen, on the prairie that winter. They referred to him as “Frozen On The Prairie.” Beede suspects that this man had an unsuccessful bison hunt, and as he lay dying in the cold, that he shot himself rather than succumb to a slow freezing death in the open. It is also possible that the man was shot by an enemy and left for dead.

The Lakȟóta text clearly indicates that the Huŋkphápȟa came across frozen bison meat that winter. High Dog’s depiction indicates that a man was shot. There is no name glyph that accompanies the pictograph, nor is there anything to distinguish the dead man.

1830: Kagi wicosa 8 wicaktipi.

Kȟaŋğí wičháša šaglóğaŋ wičháktepi (Crow men eight killed-they). In a fight with the Crow, they killed eight of them.

Beede’s notes refer to this as a battle in which many were killed.

1831: Istozi kaskapi.

Ištá Zí kaškápi (Eyes Yellow imprisoned-they). They imprisoned Yellow Eyes.

The Dakȟóta referred to this particular white trader as Yellow Eyes. Beede refers to him as Trader Brown. This year Yellow Eyes shot and killed a Dakȟóta man who drove him to jealousy on account of the man’s indiscretion with Yellow Eyes’ wife. This was considered a just penalty for such an offense, however, such was seldom committed.

Yellow Eyes is likely to be the Lakȟóta name for the trader Thomas Lestang Sarpy, aka Thomas Leston. Leston took a Sičáŋğu woman as his wife and had a son by her, his name too, was also Ištá Zí (Yellow Eyes).[29]

1832: Fitopa ablecakogopi.

Thí tȟáŋka obléča káğapi (Lodge big square-sides built-they). They built a large cabin.

It was the first time a log cabin was built by a Lakȟóta.

1833: Wicogipi akicam ina.

Wičháȟpi okhíčamna (Star whirling-around). The stars moved all around.

According to Beede, this year’s fantastic star fall caused great concern for all who witnessed it. Beede says the Lakȟóta feared that Wakȟáŋ Tȟáŋka (the Great Mystery) had lost control over creation.

Rev. Buechell notes a star fall or meteor shower as Wičháȟpi Hiŋ ȞpáyA, or Stars In A Reclining Way.[30]

1834: Wapaha he tu kogapi.

Wapȟáha hetȟúŋ káğapi (Warbonnet to-have-horns made-they). They made a warbonnet with horns.

Some of Beede’s informants say that this was the first time they made what is called a shaved horn warbonnet. Beede elaborates that this type of headdress symbolized the “vain hope” to resist the destruction of their race.

The shaved horn warbonnet, split horn warbonnet, or simply the horned warbonnet, utilized a horn which was split and carved down, or shaved, into two equal sized horns which were rubbed with red ochre and then applied to crown of the warbonnet on each side of the brow. This type of warbonnet also included a split trailer, or double trailer, which allowed for the ends to fall on either side of a horse’s rump when riding.

Warbonnets, including the split horn warbonnet, would often include winter white ermine skins which signified bravery. The ermine was known to confront animals twice its size.

The horns imbued the strength of the bison into the warbonnet. It was also the custom of split horn warbonnet wearers to personalize their bonnet with items such as beaded turtle effigies (which contained their čhekpá, or navel), clusters of feathers or plumes on the crown, or abalone shell on the cape of the trailers. The bison tail might be sewn onto the skullcap of the bonnet.

The horned warbonnet was sometimes made with one single trailer. The interior of this single trailer was adorned with pictography of animals to lend their strength to the wearer, or pictography telling his life story.[31]High Dog’s pictograph depicts this horned warbonnet with one single trailer.

The feathers were affixed to the trailers so that the top half were placed facing one direction and the bottom the opposite. Wearers of such warbonnets were usually society leaders. Sitting Bull wore such a headdress, which signified that he was the leader of the Midnight Strong Heart Society.[32]

According to Swift Dog, the Huŋkphápȟa killed an enemy who wore a shaved horn headdress and they adopted its use for themselves.[33]

1835: Wiciyelo wicakasatapi.

Wičhíyela wičhákasotapi (Upper-Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna massacre). The Upper Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna Dakȟóta experienced a massacre.

Beede’s informants tell him that there was a fight amongst the Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna Dakȟóta and many were killed, but he suspected that the fight was against white men and the whites were killed. The informants also say that some of the Dakȟóta were ready to yield, others were prepared to “kiss the gun” in defiance of the whites’ arrogance.

The pictograph for this entry depicts a figure, behind which is a travois. Four of the dead are depicted by their heads alone above the travois, indicating that they brought their dead back this way.

1836: Palani 6 wicakte pi.

Pȟaláni šákpe wičháktepi (Arikara six men-killed-they). They killed six Arikara.

Beede’s notes say that they killed six “Crow,” despite the fact that the text he recorded clearly says it was Arikara. The pictograph for this year depicts Crow as opposed to Arikara who were killed. The text for this year should be “Kȟaŋğí šákpe wičháktepi,” meaning that they killed six Crow.

Howard’s interpretation agrees with Beedes’ in that they killed six Crow, but adds that the six were chiefs.[34]

1837: Wicogaga.

Wičháȟaŋȟaŋ (Smallpox). Smallpox.

This summer the steamboat, S.S. Saint Peter, knowingly spread the smallpox threat to all the people it came into contact, particularly the native people who had little immunity to this deadly disease. By summer’s end, all the tribes living in the Missouri River basin or nearby were affected.[35]

Howard includes the narrative that smallpox carried many off to the spirit world.[36]

1838: Sunpile ska awicakilipi.

Šuŋgléška áwičhaglipi (Horse-spotted captured-returned-they). They returned with spotted horses.

They took many spotted horses in battle with the Crow.

1839: Wikite wan icikte kin.

Wíŋkte waŋ ič’íkte kiŋ (Effeminate-man [homosexual/transvestite] an suicide the). A wíŋkte committed suicide.

Beede’s notes say that a woman killed herself because her husband was killed by a white man. It was was a love-romance act. Beede either didn’t know what a wíŋkte was, or ignored the fact (as a priest) that a man was in love with another man and killed himself after his lover died.

High Dog clearly depicted a figure wearing a dress, but with the addition of a phallus, in the act of hanging him/herself. According to White Bull, this wíŋkte was known as Pȟeží (Grass).[37]

1840: Ikitami heraka ktipi.

Uŋktómi Heȟáka ktépi (Spider Elk killed-they). They [the enemy] killed one of their own whom they called Elk Spider.

Beede’s informants tell him that Uŋktómi Heȟáka was a Huŋkphápȟa chief, and that he was killed in combat by the Crow.

1841: P S a ahampi.

Psóhaŋpi (Snow-shoes). Snowshoes.

It was a deep snow winter.

1842: Hahe spe la wanktepi.

Hóhe Ošpúla waŋ ktépi (Assiniboine Cuttings/Leavings a killed-they). They killed Leavings, an Assiniboine.

Beede’s handwritten notes offer an interesting translation of this year as Assiniboine Dwarf/Little/Deformed they-killed.

The pictograph shows a scalped man. There is nothing to indicate it was an Assiniboine.

1843: Hetapa kilisin.

Hé Tópa glí šni (Horn Four return not). Four Horns did not return.

According to Beede’s informant, a chief was lost in combat with the Crow, and was thought to have died. He later returned victorious with a Crow horse. They kept a bison skull in the thípi that year. Lone Dog says that it was the Itázipčho who kept a bison skull in their lodge and made medicine to bring the buffalo.[38]The pictograph for this year’s entry, however, only refers to Four Horns.

Four Horns was a recognized leader of five Huŋkphápȟa bands: Tȟaló Nap’íŋ (Meat Necklace), Khi GlaškÁ (Tie One’s Own In The Middle), Čhegnáke Okhísela (Half Breechcloth), Šikšíčela (Bad Ones), and the Itázipe ŠíčA (Bad Bows).[39]

White Bull said that the family of Four Horns, believing that he was dead, had a memorial feast and gave-away everything they had in his memory.[40]

1844: Nawiasile.

Nawíčhašli (Measles). Measles.

They were struck with measles that year, but there was no great mortality.

1845: Ikim wocoapi.

Igmútȟaŋka wičhóhaŋpi (Cat-big [Mountain Lion] among-them-they). Some mountain lions came among them.

They killed seven mountain lions in Ȟesápa. The Crow still contested Ȟesápa as their territory at that time and killed seven Lakȟóta in retaliation for the mountain lions.

Beede’s informants tell him that there was a small band of Shoshone who lived west of Ȟesápa, and who were on friendly terms with the Crow. They tell Beede further that it was this band of Shoshone whom Sacagawea, the native woman who accompanied the Corps of Discovery, was taken from and not the nation of Shoshone further west. The Lakȟóta knew Sacagawea as Zitkála Wiyáŋ, which translates simply as Bird Woman.

1846: Tabubu alawapi.

Tabú’bu alówaŋpi (Something-Large-And-Unknown sang-over-someone-they). They sang in honor over a man about something large.

One man, entirely alone, defended the staff, the Lakȟóta flag, against great odds in combat against the Crow. Beede supposes that the “real” explanation is that the Lakȟóta adopted a more rigid system of respect for the leader “class,” those who wore feathers. His informants tell him that respect for traditional leadership was eroding with the advancing of white men, which led to the people in not holding the feather in high respect. The basis of traditional government was in danger, and with this, the nation too.

Rev. Eugene Beuchel’s “Lakota English Dictionary” translates Tabú’bu as “something large and big that no one ever saw,” but also describes this particular word as when children pile robes on another child so that the one child becomes something big.[41]It may be this last that describes this one man’s battle the Crow, against great odds that none could describe, and he came out victorious.

Howard interprets Tabú’bu as “Humpback,” and the pictograph to represent Huŋkálowaŋpi (Adopted-person-singing-over-they), in which the one holding the quirt is taking the other figure as his relative.[42]

The pictograph depicts a man holding what appears to be a notched horse quirt above or towards the other figure.

1847: Sino zkipato wakipa el wanityi.

Šiná Okhípatȟa Wakpá él waníthipi (Robe To-Piece-Together [Quilt] Creek at winter-camp). Their winter camp was at Blanket Creek.

The Huŋkphápȟa made winter camp along a creek. They had recently obtained many wool trade blankets and named the creek after their acquisition.

The pictograph depicts a blanket, one half of which appears to be dark blue and the other half is red. The blanket is next to lodge poles arranged for camp. Beede remarks that Blanket Creek is in South Dakota. The Dakȟóta referred to a same creek in SD as Šiná Tȟó Wakpána.[43]It is possible that this is the same creek.

1848: Winya wayako wicaynzapi.

Wíŋyaŋ wayáka wičháyuzapi (Woman prisoner [a]-man-seized-her-for-his-wife-they). They seized a woman, and one man took her for his wife.

The Crow seized a Huŋkphápȟa woman, and took her as his wife.

1849: Wanaseta natahi.

Wanáseta natáŋ ahíyu (Bison-hunting charge chase-towards-here). They went on a bison hunt for meat and were ambushed.

They went to hunt bison for meat and were ambushed by the Crow.

1850: Kewayuspata.

Khéya OyúspA t’Á (Turtle Catch died). Turtle Catcher died.

Beede’s informants tell him that Khewóyuspa was a chief. He died. The pictograph reveals depicts a common man holding onto, or catching, a turtle by its tail.

1851: Wayaka Paho el waniti.

Wayáka Pahá él waníthipi (Prisoner Butte at winter-camp). They made winter camp at Captive Butte.

Beede’s notes refer to this site as “Slave Heart Butte,” and also that its location is in South Dakota. There is a Slave Butte in South Dakota, located north of present-day Newell, SD. The Lakȟóta killed some Shoshone captives there long ago.

1852: Psa akiya akili alakata.

Psá[loka] akhíyA aglí wólakȟota (Crow [as the Lakȟóta pronounce this word] to-confer-in-a-group return-in-a-group peace-time).

Beede’s informants told him that there was distemper (fever and coughing) during the winter. This same winter the Lakȟóta made a treaty with the Crow.

It is interesting to note that the Lakȟóta referred to their long-time enemy as Psáloka, the Lakȟóta word for Apsáalooke (which they call themselves), rather than Kaŋğí, the Lakȟóta word for Crow.

Lone Dog says they exchanged pipes at this meeting.[44]

1853: Hetopa an waktipi.

Hé Tópa waŋ waktépi (Horn Four in-particular to-have-done-killing-in-battle-they). In a fight, in which they returned victorious, Four Horns had killed them.

Four Horns, a Huŋkphápȟa itȟáŋčhaŋ (chief), led the Lakȟóta in victory against the Crow. White Bull says this fight was at White Earth Creek, ND, north of Fort Berthold.[45]

At was around this time that Four Hours was selected as one of four Huŋkphápȟa shirt-wearers (a responsibility similar to a magistrate or other judicial leader). The other three were: Hé Lúta (Red Horn), Čhetáŋ Hó Tȟáŋka (Loud Voice Hawk), and Tȟatȟóka Íŋyaŋke (Running Antelope).[46]

1854: Mato cante ktepi.

Matȟó Čhaŋté ktépi (Bear Heart killed-they). They killed Bear Heart.

Bear Heart was killed by a Crow.

1855: Putihi sko wa akijija.

Phuthíŋhiŋ Ská awáŋkičiyaŋka (Beard White to-look-after-somebody). They took care of White Beard.

A white man with a long white beard camped with them, and they took care of him through the winter. Beede says this man’s name was John Johnson, but it is likely to be a reference to Gen. Harney who went to make peace with the Oóhenuŋpa (Two Kettle), Húŋkpathi (Lower Yankton), Huŋkphápȟa, Sihásapa (Black-Soled Moccasins; Blackfeet Lakȟóta), Mnikȟówožu (Planters By The Stream), Itázipčho (Without-Bows; Sans Arc), Iháŋktȟuŋwanŋa (Yanktonai), and Sičháŋğu (Burnt-Thigh; Brule), in March, 1856, so that settlers on the Oregon Trail might pass by unperturbed.[47]

1856: Wapaha wan yukisapi.

Wapȟáha waŋ yuk’ézapi (Warbonnet in-particular to-shear-off-they). In a fight, he sheared a warbonnet off [the enemy’s head].

Good Bear tore a warbonnet off of a Crow’s head in a fight. The pictograph depicts a Crow on horseback wearing a shaved horn warbonnet, a Lakȟóta rider behind with a lance chases his enemy.

1857: Ata kte pi akilipi.

Áta ktépi aglípi (Entire killed-they returned-they). They returned having killed all of them.

They returned from battle with the Crow, having killed all of them (the enemy war party). The pictograph indicates that the war party also counted coup three times.

1858: Pato pi Pte so wa a.

Hé Tópa pté sáŋ waŋá (Head Four female-bison dull-white then-at-that-time). Four Horns got a white bison cow that time.

Beede’s notes say that it was a man named “Paunch” who killed a white bison cow. According to White Bull, Four Horns killed this white bison at Pahá Zizípela (Slim Buttes), SD.[48]

The Lakȟóta informed Frances Densmore that the white bison was swift and especially wary, because of this and also because it was rare, it was very difficult to acquire. The fur was exceedingly soft and fine; its horns smooth and glossy. The hooves of the white bison were somewhat pink, as was its nose. The last white bison hide seen near the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation was killed by the Huŋkphápȟa along what was once called Íŋyaŋwakağapi Wakpá (Stone Idol Creek; Spring Creek).

The Iháŋktȟuŋwaŋna used to live on the east side of the Mníšoše. Once they were forced to live on the west bank of the river, the name of that creek was displaced as well. Today, Íŋyaŋwakağapi Wakpá is now known as Spring Creek[49]; it is within the vicinity of Pollock, SD. The creek today which bears the name Stone Idol Creek is a tributary of the Cannonball River. It is the first by which the Huŋkphápȟa killed their last white bison.[50]

1859: Simka ham skaktepi.

Šúŋka HáŋskA ktépi (Dog Long killed-they). They killed Long Dog.

Beede’s informants tell him that Long Dog was killed by the Crow. The Blue Thunder Winter Count says that Long Dog and Jumping Bull were killed in a fight with the Assiniboine. A war party of eight went out and only Red Robe returned.

1860: Kaginigi su toyapi.

Kaȟníȟniȟ siŋtéyapi (Choose-selectively tail-to-have-for-they). They carefully chose a [horse] tail for themselves.

Beede’s interpretation is that a man named “Race Horse” killed ten race horses. The horse depicted is a male buckskin which was killed by an arrow. There is no indication that ten horses were killed, only the one, nor who killed the horse.

In a discussion with Great Plains cultural expert, Mr. Butch Thunder Hawk (Standing Rock), this year likely represents the creation of a horse memorial, commonly known as a horse dance stick, which was carved horse effigy. Makers of these Horse Memorials carefully selected horse hair from the tail of the horse and removed a modest strip of the horse’s flesh with hair on, which was scraped and cleaned, and was affixed to the carving. It may be hung in a special place in the lodge or home, or even sometimes danced with at the wačípi (pow-wow).

No Two Horns referred to these horse sticks as “Tȟáwa Šúŋkawakȟaŋ Ópi Wokíksuye,” or “A Memorial To His Wounded Horse.”[51]

In July, 1920, Col. Alfred Welch recorded the use of a different kind of horse stick. These were simple branded sticks which were presented at a give-away. These branded sticks designated to gift recipients that they could select for themselves a horse from the givers’ herds. These horse sticks were not elaborately carved nor decorated beyond bearing a brand.[52]

1861: Itu kaso luto ktepi.

Itȟúŋkasaŋ Lúta ktépi (Weasel Red killed-they). They killed Red Weasel.

There are two explanations for this year’s event. The first being that a man named, according to Beede, Tracks Weasel, was killed in a fight with the Crow who had stolen horses from them. Beede’s interpretation suggests that the image of Red Weasel also contains within it his phallus. Beede says that the true explanation is that this year’s entry signifies the first time a sexually transmitted disease came among them, but doesn’t say which disease, only that it came from white men.

1862: Hahe 20 wicakte pi.

Hóhe wikčémna núŋpa wičháktepi (Assiniboine ten two men-killed-they). They killed twenty Assiniboine.

Beede’s interpretation is that the Lakȟóta fought and killed twenty “HAKES,“ which he interprets as Creeks. The pictograph suggests, instead, that the Lakȟóta war party killed twenty Crow.

Frances Densmore recorded a song which was sung in pursuit of the Crow shared by Swift Dog and Kills At Night who recounted a song in their pursuit of the Crow:

Eháŋna Long-Ago (Long ago)

Hečhámuŋ kte č’uŋ Thusly to-do afore-said (I would have done this)

Núŋmlala kešá Only-two no-matter-which (Only twice again)

AwápȟA peló To-strike-people they-are-coming (I struck them [the enemy])

Hó! Now! (Now!)

Nayáȟ’uŋpi huwó? You-hear question? (Do you hear it?)[53]

1863: Taka kuwa wan kte.

Tȟóka khuwá waŋ ktépi (Enemy chase particular-one killed-they). They chased one of the enemies and killed him.

In a fight with the Crow, they found a Crow youth in a coyote trap and killed him. The pictograph suggests that the one who chased him counted first coup. It also seems evident that the Crow youth was known to them as Yellow Weasel.

1864: Wayaka wiyapeyapi.

Wayáka wiyáŋ iyópȟeyapi (Captive woman exchange-for-they). They exchanged a captive woman in trade.

They captured and held a white woman. They refused to give her up because they believed her to be good luck. This is probably Fanny Kelly. The Oglála had captured Kelly at Box Elder Creek in Wyoming. She was stolen from the Oglála by the Sihásapa and made the wife of Brings Plenty. Kelly was given the name “Real Woman.” She eventually regained her freedom either by tricking her Lakȟóta captors into bringing her to Fort Sully (present-day Pierre, SD), or she was was escorted to Fort Sully, willingly, by a Huŋkphápȟa man and under the protection of Sitting Bull himself.[54]

1865: Leje awicaya.

LéžA awíčhoyazaŋ (to-pass-water-often sickness-on). A sickness struck, which causes one to urinate frequently.

Beede’s notes reveal that he believed this was caused by a sexually transmitted disease. A urinating phallus appears in this pictograph. Beede’s informants told him that blood was involved. This sickness could also have been a urinary tract infection, but what caused it is unknown.

1866: Pizi capapapi.

Phizí čhapȟápȟapi (Gall stabbed-they). They stabbed Gall.

Gall was stabbed twice and left for dead near Fort Berthold in November of 1865. He recovered. When the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty was brought to Fort Rice, D.T., for the Huŋkphápȟa to sign, Gall showed Fr. DeSmet his bayonet scars. Gall realized that the treaty meant conceding more land to the whites, and though he signed the treaty (as Goes In The Middle), perhaps even unknowing what he was signing after being feasted and gifted, the first thing Gall said when offered the chance to speak to the officials was, “You ask me where are our lands? I answer you. Our lands are wherever our dead are buried!”[55]Gall would later lead the defense of the Huŋkphápȟa at the Little Bighorn fight and routed Major Reno’s assault.

1867: Winya wan hu wakise.

Wiyáŋ waŋ hú waksé (Woman a leg severed). A woman’s leg was severed.

A woman died, over in Montana, after her leg was severed.

1868: Itazipica ake zapi ta.

Itázipčho akézaptaŋ t’Á (Without-Bows fifteen died). Fifteen members of the Itázipčho (Sans Arc) died.

Only five Lakȟóta are shown on this year’s entry. Beede’s notes say that it was actually fifteen Crow who were killed in this fight. According to Brown Hat the Crow killed fifteen Itázipčho and a Khulwíčaša (Lower Brule) named “Long Fish.”[56]

1869: Kanigi wicasa zo wicaktepi.

Kȟaŋğí wičháša wikčémna yámni wičháktepi (Crow men ten three men-killed-they). They fought and killed thirty Crow men.

They killed thirty Crow. The pictograph, however, only shows fourteen.

1870: Kangi wiyakota.

Kȟaŋğí WíyakA t’Á (Crow Feather died). Crow Feather died.

Crow Feather, an itáŋčhaŋ (leader), died of natural causes.

1871: Kangi cigala to.

Kȟaŋğí Čík’ala t’Á (Crow Little died). Little Crow died.

Little Crow died. This is not the same Taóyate Dúta (His Red Nation; aka “Little Crow”) who was involved in the 1862 Minnesota Dakota Conflict. The Isáŋyathi Little Crow was shot and killed by a settler in July of 1863.

1872: Mata kawige ti hi wankte.

Matȟó KawíŋğA thí hí waŋ kté (Bear Turns-About lodge comes-here a killed). Circling Bear killed [an enemy] who came to his lodge.

Circling Bear (also Circle Bear) killed a Crow who came to his lodge to fight. Turning Bear, an Itázipčho, was a participant in the Little Bighorn fight, a Ghost Dancer leader, and a witness of the Wounded Knee massacre. The Carnegie Museum winter count depicts the death of Turning Bear in the winter of 1912-1913 when he was run over by a train.[57]

1873: Ikacolo towa wan eyayapi.

Íkačhaŋla tȟáwa waŋ iyéyapi (Trot-little his a found they). They found his horse which was trotting with a light gait.

A Crow stole a white horse from someone. They found the horse trotting lightly.

1874: Taka cepa wan ktepi.

Tȟóka čhépa waŋ ktépi (Enemy fat a killed-they). They killed a fat enemy.

They killed a fat Crow. Afterward, they dissected the body in hopes of discovering why or how he had grown so large. According to Beede, a member of the St. Luke’s Episcopal community had participated in the dissection of the Crow, and believed that the body weighed somewhere around 400 lbs. Beede’s informant also said that the flesh was very thick and yellow in color.

1875: Sunko ska hikin.

Šuŋgská hí kiŋ (Dog-White came-here the). White Dog came here.

According to Beede, they were visited by “Apache” that summer, who rode white horses. The pictograph, however, indicates a Crow named White Horse instead. Beede’s handwritten notes say that this was an Assiniboine chief. The Lakȟóta word for Apache is Čhíŋčakiŋze (Squeaking Wood).

Perhaps Beede was meant Arapaho, who were allied with the Thítȟúŋwaŋ and Šahíyela (Red Talkers; Cheyenne) at the Little Bighorn fight. The Lakȟóta word for Arapaho is Maȟpíya Tȟó (Blue Cloud). How or why Beede concluded it was the Apache who came is not clear. The pictograph for this year is a Crow with a name glyph of a white horse or a white dog.

According to White Bull, this was an Assiniboine chief they knew as White Dog.[58]

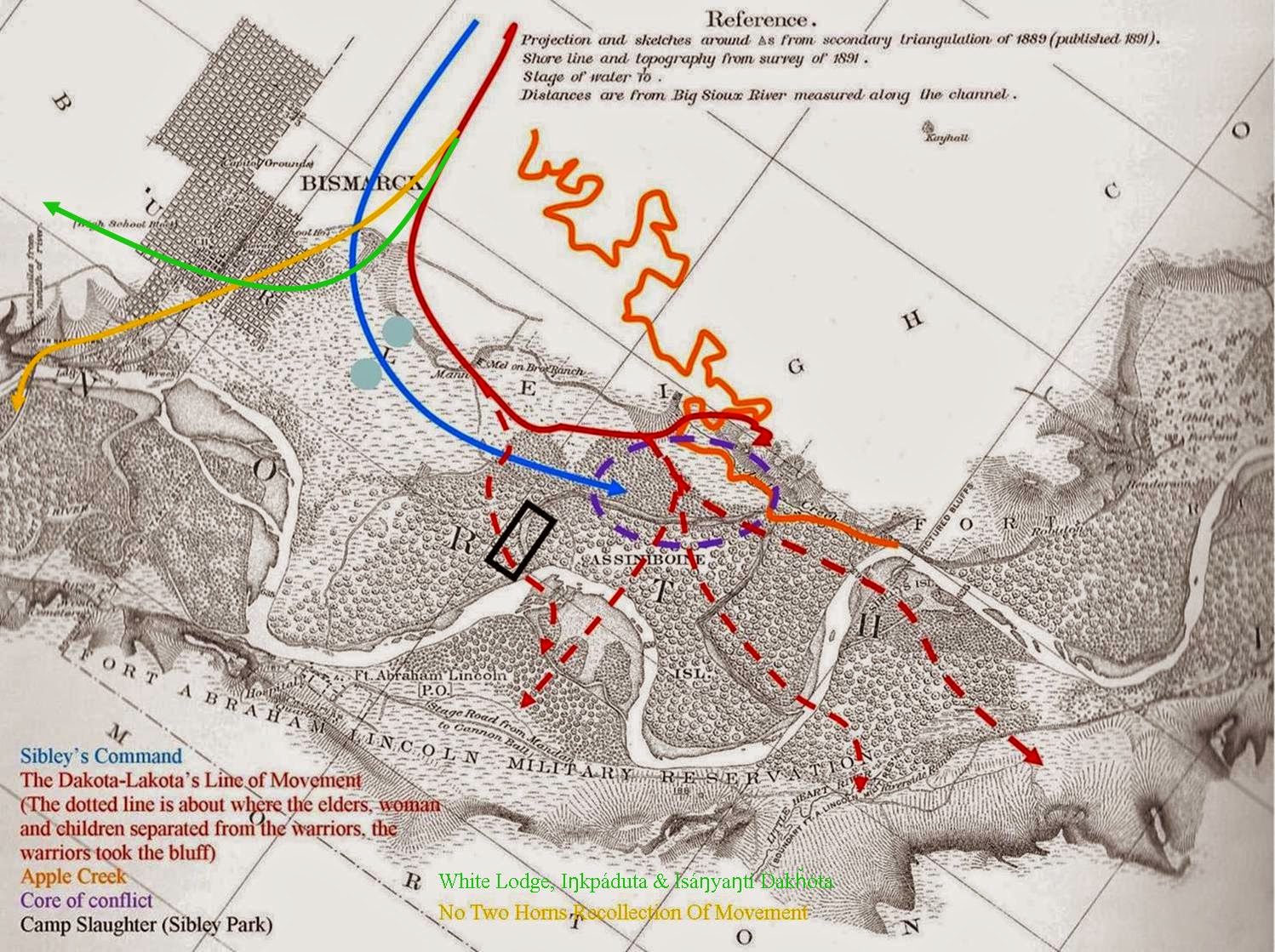

1876: Tatka iyato ke tako akileso ab.

Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake táku Ógleša ób (Bison-Bull Sitting something Coat-red with-them). Sitting Bull did something [an agreement] with the Redcoats.

Sitting Bull made an agreement with the Canadian military at Fort Walsh in Canada, following the Little Bighorn fight, for the Huŋkphápȟa to stay there. The Lakota began arriving to the fort in November, 1876, and throughout the winter and spring the following year. Canada refers to this event as the Lakota Refugee Crisis.

Canada regarded the Lakȟóta as “Americans.” Sitting Bull argued that the Lakȟóta were allies of the English, who still managed Canada’s foreign affairs, in the War of 1812.[59]

1877: Wicagipi wanjilo ktepi.

Wičáȟpi Waŋžíla ktépi (Star Only-One they-killed). They killed One Star.

One Star was killed in a fight with the Crow.

1878: Mata cigatato ahiktepi.

Matȟó Čík’ala ahí ktépi (Bear Little came-here killed they). They came and killed Little Bear.

Little Bear was killed in a fight with the Crow.

1879: Tawahu kezalutoto.

Tȟáwahukheza Lúta t’Á (His-Spear Red died). His Red Spear died.

He Has A Red Spear died.

1880: Pizi ti.

Phizí thí (Gall lodge). Gall lodge.

Beede’s informants say this this year, only two words, is when Gall intervened during a sundance near Fort Yates, ND. Beede refers to this as a “remarkable feat of bravery.” Beede’s handwritten notes say that Gall shot at the camp on Tongue River.

Frank Zahn, Howard’s informant, says that this year represents when soldiers shot into Gall’s camp on Tongue River.[60]

Gall and his followers, Crow King, Black Moon, Low Dog, and Fools Heart, and their extended families (a total of 230 people) were brought to Standing Rock Agency in the summer of 1881.[61]

1881: Pehi ska kin Napeyuzapo.

Pȟehíŋ Ská kiŋ napéyuzapo (Hair White the handshake-with-all-of-them). The White Hair shook hands in greeting with all of them.

A white man they called White Hair (Maj. James McLaughlin) led the Lakȟóta to feel friendly towards the government, with mixed success. McLaughlin was the superintendant of the Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation. Beede’s notes refer to McLaughlin as White Beard.

1882: Pehi ska kici wanasapi.

Pȟehíŋ Ská kičhí wanásapi (Hair White with big-game-[bison]-hunt-they). White Hair went on a bison hunt with them.

White Hair went bison hunting with the Lakȟóta.

White Hair (McLaughlin) supervised the last great bison hunt in North America in the summer of 1882. The hunting party consisted of about 600 mounted Lakȟóta. Francis Densmore briefly, yet optimistically, describes the few years’ acquaintance between Sitting Bull and McLaughlin.[62]

1883: Kangi wicaso 3 hipi.

Kȟaŋğí wičháša yámni hípi (Crow men three came-they). Three Crow men came to them.

Three Crow came to visit them as friends.

1884: Kangi cigaloto.

Kȟaŋğí Čík’ala t’Á (Crow Little died). Little Crow died.

Little Crow died. According to White Bull, this is Kȟaŋǧí Yátapi (Crow King) who died. Crow King led eighty warriors against the 7thCavalry in the Little Bighorn fight.[63]He died of consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis) and was buried according to Roman Catholic sacraments.[64]

1885: Iceta Wahacakata.

Čhetáŋ Waháčhaŋka t’Á (Hawk Shield died). Hawk Shield died.

An old warrior named Hawk Shield died. Howard suggests that this may be Flying By.[65]

1886: Herako 1897

Heȟáka Wašté t’Á (Bull-Elk Good died). Good Elk died.

Good Elk died. This year also begins including the year of the Common Era.

1887: Hetapo to 1898.

Hé Tópa t’Á (Horn Four died). Four Horns died.

Four Horns died.

Following the Little Bighorn fight, Four Horns led the Huŋkphápȟa under his leadership to Fort Walsh in Canada. He was among the Huŋkphápȟa who journeyed to Fort Buford, Dakota Territory, in 1881. Four Horns and his immediate family were held as prisoners of war at Fort Randall where his wife died. The Huŋkphápȟa prisoners were eventually taken to Standing Rock to be with the Huŋkphápȟa there. According to the Indian census Four Horns was seventy-three winters.[66]

1888: Wisapata 1899.

Wí SápA t’Á (Luminary [i.e. Sun/Moon] Black died). Black Moon died.

There was a solar eclipse this year on New Year’s Day, Jan. 1, 1889, however, this year’s entry indicates that it was the Huŋkphápȟa chief, Black Moon, who died. The pictograph clearly depicts a man with a name glyph above his head. The name glyph depicts an inverted black crescent representing a solar eclipse.

Black Moon met the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty commission at Fort Rice to declare his desire for peace on the condition that the the Great Father halt the construction of the Northern Pacific Railroad and recall his soldiers. He fought in the Little Bighorn conflict, and was among the Huŋkphápȟa who returned from Canada with Gall.

The Lakȟóta have many ways to describe the solar eclipse. The Huŋkphápȟa also refer to the solar eclipse as Maȟpíya Yapȟéta which means “Fire Cloud.” About ten other Lakȟóta winter counts refer to the solar eclipse of 1869 as Wí’kte (The Sun Died; Death Of The Sun).

According to Mr. Warren Horse Looking Sr. (Sičáŋğu), the solar eclipse is Aŋpétuwi Tokȟáȟ’aŋ, or “The Disappearing Sun.” Mr. Jon Eagle (Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate) says Wí’Atá (The Sun Entire). Ms. Leslie Mountain (Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate) learned to refer to the solar eclipse as WakhápheyA (Of A Singular Appearance).

The New Lakota Dictionary interprets a solar eclipse in the Lakȟóta language as: Aháŋzi (Shadow) and AóhaŋziyA (To Cast A Shadow Upon).

1889: Kawakata el winyawicaka 1890.

Kawéğata él wíŋyaŋ wičháktepi (To-break-off-on at woman a-died-they). Something fell on a woman of theirs and killed her.

A woman was killed when a tree collapsed onto her.

Used As A Shield said of the summer of 1889, “This was the last time that Sitting Bull was in a regular tribal camp...used to go around the camp circle every evening just before sunset on his favorite horse, singing this song:”

Ikíčhize Warrior (A Warrior)

Waóŋ’kȟoŋ Have-been (I Have been)

Waŋná Now (Now)

Henála yeló It-is-finished (It is all over)

Iyótiye khiyá Difficult-time (A hard time)

1890: Tatoka iyatake kte pi 1891.

Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ktépi (Bison-Bull Sitting killed-they). They killed Sitting Bull.

They killed Sitting Bull that winter.

As Sitting Bull was arrested, he paused at the door of his cabin and sang a farewell song, “I am a man and wherever I lie is my own.” Moments later, he lay dead outside the door of his home; six members of Midnight Strongheart Society also died that morning.[68]

Red Tomahawk offered this frank, brutal, and succinct account:

Sitting Bull was my friend. I killed him like this...

At the time of the death of Sitting Bull I was second lieutenant of the Indian Police at Fort Yates. The Indian police were ordered to go out and bring him in dead or alive. We found him with about 500 men out on the banks of the Grand River, about thirty miles from Fort Yates. The Indians in the party were holding a ghost dance, which the government had prohibited. The Indian police went over to where the camp was and told them to stop the dance, but they did not do so. Captain Bull Head, Sergeant Shave Head and myself [sic] went over and stood beside Sitting Bull and I grabbed Sitting Bull’s left arm and held him. One of Sitting Bull’s men fired and shot Bull Head. When I saw him sinking to the ground I drew my revolver and shot Sitting Bull twice, once through the left side and once through the head. We broke up the dance and Sitting Bull was taken back to the agency dead.[69]

In Fort Yates, 1915, Colonel Alfred B. Welch interviewed Tačháŋȟpi Lúta (Red Tomahawk), who asserted to Welch that his name meant [His] Red War Club. Welch spoke with Red Tomahawk about the death of Sitting Bull. "I was under orders," Red Tomahawk said to Welch, "so I killed him. He should not have been hollared [sic]."

Welch asked if Sitting Bull's spirit ever returned there. "Yes. Sometimes," replied Red Tomahawk, "He rides in on an elk spirit." Welch wanted to visit Sitting Bull's burial site and asked Red Tomahawk to go with him there. Red Tomahawk declined the invitation and ended the interview with, "No. I do not go. I am afraid. There are mysterious flowers upon his grave every year. We do not know where they come from. They are wakȟáŋ."[70]

1891: Tasuke heratota 1892.

Tȟašúŋke Híŋȟota t’Á (His-Horse Roan died). Roan Horse died.

Spotted Horse died. He was a follower of Chief Circle Bear.

1892: Sinko mazata 1893.

Šúŋka Máza t’Á (Dog Iron died). Iron Dog died.

Beede’s translation says this man’s name was “Horse Shoe.”

Little is known of Iron Dog. He was a Načá (headman) who lead his Huŋkphápȟa followers to Fort Walsh, Canada, following the Little Bighorn fight. While in exile, Iron Dog had a disagreement with Sitting Bull and refused to follow his lead again.[71]

1893: Tawahu kezotuta ta 1894.

Tȟáwahukheza Lúta t’Á (His-Spear Red died). His Red Spear died.

His Red Spear died.

1894: Pizi to 1895.

Phizí t’Á (Gall died). Gall died.

Chief Gall died. Gall became a Christian and regularly attended services at St. Elizabeth’s Episcopal Church in Wakpala, SD, a farmer, a judge, and a proponent of education, going so far as to donate some of his allotment to create a day school.[72]He rests at St. Elizabeth’s cemetery in Wakpala, SD.

1895: Winya wan ilekin 1896.

Wíŋyaŋ waŋ ilé kiŋ (Woman a burn the). A woman burned [to death].

A woman burned to death in her home.

1896: Pa Wicoyukisapi 1897.

Pȟá wičháyazaŋpi (Head sickness-they). A sickness affected their heads.

A sickness caused sores on their heads. The Roan Bear Winter Count has a similar entry for 1838 in which many died of a head sickness which caused sores on their heads. This may be the hemorrhagic form of smallpox which causes extreme headaches and sudden violent death.

The pictograph for this year depicts three Dakȟóta men and a noose. The image clearly recalls the lynching and hanging of three Dakȟóta men in retaliation for the Spicer family murders across the river from Standing Rock.[73]

1897: Kangi iuiyakata 1898.

Kȟaŋğí Wíyaka t’Á (Crow Feather died). Crow Feather died.

Beede’s notes say that there was a woman who was once taken prisoner by the Crow. She then lived with them for the remainder of her life and died among them.

The pictograph for this year depicts a common man with a name glyph of a red feather.

1898: Mato cuwiyukisa ta 1899.

Matȟó Čhuwíyuksa t’Á (Bear From-The-Waist-Up died). Bear Vest died.

Beede’s notes refer to this man as “Spotted Bear” instead. Howard interprets the text as, “Bear Broken In Half died.”

The pictograph is of a common man with a name glyph that appears to be the front half of a small black bear.

1899: Ieta wahacaka ta 1900.

Čhetáŋ Waháčhaŋka t’Á (Hawk Shield died). Hawk Shield died.

Hawk Shield was a chief of the Sihásapa Lakȟóta.

1900: Herako wawaite ta 1901.

Heȟáka Hó Wašté t’Á (Elk-Bull Voice Good died). Good Voice Elk died.

1901: Tatako pa to 1902.

Tȟatȟáŋka Pȟá t’Á (Bison-Bull Head died). Bull Head died.

Beede notes that this isn’t the same Lt. Bull Head who was involved in the death of Sitting Bull.

1902: Tatako wano yi ta 1903.

Tȟatȟáŋka Wanáği t’Á (Bison-Bull Ghost died). Bull Ghost died.

Beede knew him as Buffalo Ghost.

1903: Wicaripi wanjilo ta 1904.

Wičáȟpi Waŋžíla t’Á (Star Only-One died). One Star died.

Beede interprets this as the year a star disappeared. The pictograph depicts a star.

1904: Wahacakasapota 1905.

Waháčhaŋka SápA t’Á (Shield Black died). Black Shield died).

Beede’s notes says his name was Beaver Shield. The pictograph depicts a black shield.

1905: Ite amaroju ta 1906.

Ité Omáğažu t’Á (Face Raining-On died). Rain In The Face died.

The pictograph depicts a common man whose name glyph is a pictograph of a Crow Indian.

By Rain In The Face’ own account, he was called so on two occasions as a youth. The name was deemed auspicious, when upon going to war against the Hidatsa, he had painted his face red and black to represent the sun, they had fought in the rain all day which streaked his painted face. Rain’ was known for his part in the Fetterman Fight, his infamous escape from Fort Abraham Lincoln, and for participating in the Little Bighorn fight. When the reservation era began, Rain’ put aside all his conflict with the whites and lived peaceably the rest of his days.[74]

1906: Ieto wakiuate 1907.

Čhetáŋ Wakíŋyaŋ t’Á (Hawk Thunder died). Thunder Hawk died.

According to Beede, this is Feather Hawk.

The pictograph depicts a common man wearing a red and white striped shirt. The name glyph is a yellow hawk with lightning coming out of its wings.

The prominent use of yellow in the coloring of the name glyph and the deliberate black lines upon the head, wings, and tail, seem to hint at this depiction being a Čhaŋšíŋkaȟpu (Yellow Winged Woodpecker).

The Lakȟóta associate the Čhaŋšíŋkaȟpu with the Wakíŋyaŋ (Thunder-Beings), in the black crescent moon upon its breast and black hailstone upon its body. In fair weather, Čhaŋšíŋkaȟpu is said to proclaim, “Aŋpétu wašté, aŋpétu wašté [It’s a beautiful day, it’s a beautiful day!].”[75]

1907: Tadukeiyake to 1908.

Tȟašúŋke ÍŋyaŋkA t’Á (Horse To-Run died). Running Horse died.

Beede’s notes say his name is His Horse Rears. The pictograph depicts a name glyph of a running horse above a common man.

1908: Tyacukaske suwakipimoin 1909.

Tȟašúŋkaška wakpámni (Horses-staked a-distribution-of). Horses were issued.

According to Frank Zahn, horses were issued to the Lakȟóta at Rock Fence Place, south of Fort Yates, ND.[76]

1909: Wico gipi wan ile yahan 1910.

Wičáȟpi waŋ ilé yÁ haŋ (Star a burn go night). A burning star went into the night.

This is in reference to Halley’s Comet.

1910: Fata ko witka ta 1911.

Tȟatȟáŋka Witkó t’Á (Bison-Bull Crazy died). Crazy Bull died.

1911: Note:The last entry of the High Dog Winter Count appears to be two separate events which occurred in the same year.

Wakaheja nasilipi 1912.

Wakȟáŋheža našlípi (Children measles-they). Measles struck the children.

Wicarpi wan ileyoukin.

Wičáȟpi waŋ ilé ú kiŋ (Star a burn coming-here the). A burning star came this way.

There appeared at least six comets in 1913 as recorded and observed by H.C. Wilson and C.H. Gingrich at Carlton College, M.N. The entry for this year may reference Comet 1913a which was visible to the naked eye in May and June of 1913.[77]

The pictograph depicts a common person whose body is adorned with red spots, but whose face is unmarked. A falling star is depicted close enough to be a name glyph, but there is no marker connecting the two.

[1] Welch, Col. Alfred B. "Chapter 7: Blue Cloud Stone." www.welchdakotapapers.com. October 13, 2013. Accessed February 1, 2015. [2]New Lakota Dictionary, 2ndEdition, s.v. “Hakéla.” [3]Šuŋgmánitu-Išná (Lone Wolf). "Lakota Birth Order Names." The Lodge of Šuŋgmánitu-Išná. January 1, 1998. Accessed February 2, 2015. [4]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 352. [5]Mallory, Garrick. "Chapter X: Chronology." In Picture-Writing Of The American Indians, 319. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1972. [6] Howard, James H. "Yanktonai Ethnohistory And The John K. Bear Winter Count." Plains Anthropologist: Journal Of The Plains Conference 21, no. 73, Pt. 2 (1976): 22. [7]"4: Winter By Winter." In The Years The Stars Fell: Lakota Winter Counts At The Smithsonian, edited by Candace S. Greene, by Russell Thornton, 130. 1st ed. Lincoln, NB: University Of Nebraska Press, 2007. [8] Mallory, Garrick. "Chapter X: Chronology." In Picture-Writing Of The American Indians, 295. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1972. [9]Locke, Kevin. Online conversation with author. April 24, 2015. [10]The Indian Sign Language, First Bison Print Edition, s.v. “Scout.” [11]Mallory, Garrick. "Chapter X: Chronology." In Picture-Writing Of The American Indians, 300. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1972. [13] Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 359. [14]Beede, Rev. Aaron. "The High Dog Winter Count." notes, Fort Yates, ND, June 6, 1912. [15] Diedrich, Mark. "Chapter 4, Waneta: Dakota Dictator." In Famous Chiefs Of The Eastern Sioux, 29-42. 1st ed. Vol. 1. Minneapolis, MN: Coyote Books, 1987. [16]Mallory, Garrick. "Chapter X: Chronology." In Picture-Writing Of The American Indians, 316. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1972. [18]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 360. [19]Lakota-English Dictionary, 2nd Edition, s.v. “Wi’tapaha” and “Witapahatu.” [20]"American Fur Company Employers - 1818-1819." In Collections of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites, 154-169. Vol. 12. Madison, Wisconsin: Democrat Printing Company, State Printers, 1892. [21]Mallory, Garrick. "Chapter X: Chronology." In Picture-Writing Of The American Indians, 316. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1972. [22]Howard, James H. "Yanktonai Ethnohistory And The John K. Bear Winter Count." Plains Anthropologist: Journal Of The Plains Conference 21, no. 73, Pt. 2 (1976): 26. [24]Mallory, Garrick. "Chapter X: Chronology." In Picture-Writing Of The American Indians, 317. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1972. [25]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 365. [26] Innis, Ben. "The Heritage of Bloody Knife." In Bloody Knife: Custer's Favorite Scout, 1-9. Revised ed. Bismarck, ND: Smokey Water Press, 1994. [28]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 366. [29] Sundstrom, Linea. "The Chandler-Pohrt Winter-Count." St. Francis Mission Among The Lakota. January 1, 1998. Accessed March 3, 2015. [30]Lakota-English Dictionary, 2ndEdition, s.v. “Star.” [31]Mails, Thomas. "Hair Styles, Jewelry, And Headdresses." In The Mystic Warriors Of The Plains, 357-396. 2nd ed. Tulsa, OK: Council Oak Books, 1991. [32] Thunderhawk, Butch. Conversation with the author, April 14, 2015. [33]Desnmore, Frances. Teton Sioux Music And Culture. 1st Bison Book Edition ed. Lincoln, NB: University Of Nebraska Press, 1992. 403. [34]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 373. [35]Chardon, F.A. Chardon's Journal At Fort Clark, 1834-1839. Edited by Annie Heloise Abel. 1st Bison Book Edition ed. Lincoln, NB: University Of Nebraska Press, 1997. 123. [36]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 374. [37] Vestal, Stanley. Warpath : The True Story of the Fighting Sioux Told in a Biography of Chief White Bull. 1st ed. Boston, MA: University Of Nebraska Press, 1934. 348. [38]Mallory, Garrick. "Chapter X: Chronology." In Picture-Writing Of The American Indians, 281. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1972. [39]LaPointe, Ernie. "Jumping Badger." In Sitting Bull: His Life And Legacy, 22. 1st ed. Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, 2009. [40]Vestal, Stanley. Warpath : The True Story of the Fighting Sioux Told in a Biography of Chief White Bull. 1st ed. Boston, MA: University Of Nebraska Press, 1934. 265. [41]Lakota-English Dictionary, Bilingual Edition, s.v. “Tabú’bu.” [42]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 379. [43]Waggoner, Josephine. "Dakota And Lakota Oyate Band Organization." In Witness: A Huŋkphápȟa Historian’s Strong-Heart Song of The Lakotas, 41. Lincoln, Nebraska: University Of Nebraska Press, 2013. [44]Mallory, Garrick. "Chapter X: Chronology." In Picture-Writing Of The American Indians, 283. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1972. [45]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 383. [46]Utley, Robert M. "2: Warrior." In The Lance And The Shield: The Life And Times Of Sitting Bull, 21-22. 1st ed. New York, NY: Henry Holt And Company, 1993. [47]Reavis, L.U., and Cassius Marcellus Clay. The Life And Military Services Of Gen. William Selby Harney. 1st ed. Saint Louis, MO: Bryan, Brand &, 1878. 201. [48]Vestal, Stanley. Warpath : The True Story of the Fighting Sioux Told in a Biography of Chief White Bull. 1st ed. Boston, MA: University Of Nebraska Press, 1934. 349. [49]Nicolett, Joseph, and Lt. J.C. Fremont. Hydrographical Basin of the Upper Mississippi River from Astronomical and Barometrical Observations, Surveys, and Information. Washington D.C.: Bureau of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, U.S. Dept. of War, 1843. [50]Desnmore, Frances. Teton Sioux Music And Culture. 1st Bison Book Edition ed. Lincoln, NB: University Of Nebraska Press, 1992. 446. [51]Wooley, David L., and Joseph D. Horse Capture. "Joseph No Two Horns: He Nupa Wanica."American Indian Art Magazine 18, no. 3 (1993): 32-43. [52] Welch, Col. Alfred B. “Life On The Plains In The 1800s." www.welchdakotapapers.com. October 13, 2013. Accessed April 22, 2015. [53]Desnmore, Frances. Teton Sioux Music And Culture. 1st Bison Book Edition ed. Lincoln, NB: University Of Nebraska Press, 1992. 407. [54]Vestal, Stanley. "The Captive White Woman." In Sitting Bull: Champion Of The Sioux, A Biography, 64. 1st ed. Norman, OK: University Of Oklahoma Press, 1989. [55]Crawford, Lewis F. Rekindling Camp Fires: The Exploits Of Ben Arnold (Conner) (Wa-si-cu Tam-A-he-ca) An Authentic Narrative Of Sixty Years In The Old West As Indian Fighter, Gold Miner, Cowboy, Hunter, And Army Scout. 1st ed. Bismarck, ND: Capital Book Company, 1926. 172. [56]Mallory, Garrick. "Chapter X: Chronology." In Picture-Writing Of The American Indians, 326. 1st ed. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Dover Publications, 1972. [57]Haukaas, Thomas "Red Owl""Lakota Of The Plains: The Winter Count." www.carnegiemnh.org/. January 1, 1995. Accessed April 22, 2015. [58]Vestal, Stanley. Warpath : The True Story of the Fighting Sioux Told in a Biography of Chief White Bull. 1st ed. Boston, MA: University Of Nebraska Press, 1934. 350. [59]Coneghan, Daria. "Fort Walsh." www.esask.uregina.ca. January 1, 2006. Accessed April 22, 2015. [60]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 398. [61]Dickson III, Ephriam D. The Sitting Bull Surrender Census: The Lakotas At Standing Rock Agency, 1891. 1st ed. Pierre, SD: South Dakota State Historical Society, 2010. 48-59. [62]Densmore, Frances. "The Buffalo Hunt." In Teton Sioux Music And Culture, 436. 1st Bison Book Edition ed. Lincoln, NB: University Of Nebraska Press, 1992. [63]Vestal, Stanley. Warpath : The True Story of the Fighting Sioux Told in a Biography of Chief White Bull. 1st ed. Boston, MA: University Of Nebraska Press, 1934. 270. [64]Bismarck Tribune, April 11, 1884. [65]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 401. [66] Utley, Robert M. "20: Standing Rock." In The Lance And The Shield: The Life And Times Of Sitting Bull, 252. 1st ed. New York, NY: Henry Holt And Company, 1993. [67]Densmore, Frances. "The Buffalo Hunt." In Teton Sioux Music And Culture, 258. 1st Bison Book Edition ed. Lincoln, NB: University Of Nebraska Press, 1992. [68]LaPointe, Ernie. "The Murder." In Sitting Bull: His Life And Legacy, 104. 1st ed. Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, 2009. [69]Red Tomahawk, Brenda. "The Death Of Sitting Bull: The Story Of Red Tomahawk." Interview by author. May, 2010. [70]Welch, Col. Alfred B. "Red Tomahawk: "Sitting Bull Was My Friend. I Killed Him Like This..."" www.welchdakotapapers.com. October 13, 2013. Accessed November 14, 2014. [71]Utley, Robert M. "14: Winter Of Dispair." In The Lance And The Shield: The Life And Times Of Sitting Bull, 176. 1st ed. New York, NY: Henry Holt And Company, 1993. [72]Lawson, Robert W. "His Final Years." In Gall: Lakota War Chief, 230-238. 1st ed. Norman, OK: University Of Oklahoma Press, 2007. [73] Bueling, Lynn. "Book Recounts N.D. Mob Lynching." The Bismarck Tribune, December 1, 2013, Book Reviews sec. Accessed May 6, 2015. [74] Eastman (Ohiyesa), Charles A. "Rain In The Face." In Indian Heroes & Great Chieftains, 132-151. 1st Bison Book Edition ed. Lincoln, NB: University Of Nebraska Press, 1991. [75]Thunderhawk, Butch. Conversation with the author, April 14, 2015. [76]Howard, James H. "Dakota Winter Counts As A Source Of Plains History." Smithsonian Institution, Bureau Of American Ethnology, Bulletin 173, Anthropological Papers, no. 61 (1960): 409. [77]Wilson, H.C., and C.H. Gingrich. "Observation Of The Comets of 1913 And 1914." Publications of the Goodsell Observatory 4 (1915): 1-28.