A Visit With A Respected Tribal Historian

The Story Of Devil's Heart Butte (My 100th Post)

By Dakota Wind

I was looking at the North Dakota state map that’s pegged to my office wall. I don’t know what it is, maybe it was a recent trip out to Heháka Wakpá Makĥoche (Elk River Country, or Theodore Roosevelt National Park) and I was in the mood to learn what the Dakota-Lakota people called places before explorers, traders, and settlers arrived.

There’s a lake in the north eastern quarter of the state. It’s a fresh water lake that’s been growing and spilling onto shore property. New islands have been formed, roads have been built higher, fields are underwater, and the water threatens to rise higher without relent.

The lake is known to the Dakota and Lakota people as Mni Wakaŋ Čhaŋté. Don’t believe Wikipedia in this, if you look it up there. A word for word translation of the Dakota to English is Water With-Energy Heart, which freely translates as Spirit Heart Lake. The calque of Bad Spirit Lake is entirely a misconception.

There, on the southern bank of the Spirit Heart Lake lay the Spirit Lake Sioux Indian Reservation, home of the Spirit Lake Oyate (Nation). The Spirit Lake Oyate has about 6,700 or so enrolled members, but not all live on the reservation.

The lake, Spirit Heart Lake (aka Devil’s Lake), the people (the Spirit Lake Oyate), have a name in common with a site on the reservation near the town of Tokio (a strange word in and of itself; said to named after the Dakota word for “Toki” for “gracious gift;” the closest word for gift, is in the act of receiving a gift, “Okini;” in the discussion of naming the township, Burlington Northern Railroad officials were said to have chosen “Toki” and then added the “o,” at the end thinking, probably, of being cute). There, nestled among the rolling hills of the prairie land overlooking the lake is Spirit Heart Butte, only it’s popularly known as “Devil’s Heart Butte.”

I turned to Spirit Lake tribal historian Louie Garcia to find an answer. I’ve conversed with Louie on the phone over the years and by email. I had always thought he was perhaps a middle-aged gentleman by the youthful exuberance of his voice. Some voices age. Louie’s voice does not. He’s in his 70's, a respected member of the tribe, he’s gracious to give me an answer, and he wants me to share it with others.

Louie has asked me to post it as he sent it to me, word for word. Pilamiya pelo, Lekshi Louie! He Even included a bibliography and a glossary of Dakota terminology (at the end of this entry).

__________

Heart Hill is a treeless kame located one mile northwest of Tokio, North Dakota in Section Four Woodlake Township (T152N – R64W) Benson County. It sits on the eastern edge of the Backbone, a line of hills formed when Spirit Lake (Devils Lake) was formed some 10,000 years ago during the last ice age. With an elevation of 1725 feet above sea level it can been seen on the horizon for miles in the lake region, and from its summit one can look over a vast area surrounding this hill. The name ‘heart’ means that it is at the center of the area but also the center of spiritual knowledge. As this hill appears to be in the shape of an upside down human heart, some incorrectly speculate this as the reason for its name.

Heart Hill is the most sacred elevation in all of North Dakota. It could be considered a cathedral. This Butte de Coeur of the French fur traders is called in the Dakota language Miniwakan Cante Pahaor Heart Hill at Spirit Lake. The French fur traders named Devils Lake so that presently the term ‘devil’ is attached to many local geographical features. “Devils Heart” is the name used by local people. Naturally the ‘devil’ word is a misunderstanding, but referring to the Water Spirits who live in the lake.

This Heart Hill is a sacred location because it is the Lodge of the Water Spiritfor whom Spirit Lake is named. These spirits are called Unktehi or Terrible Ones due to their custom of drowning anyone who foolishly ventured upon the lake without their permission. These Unktehi are worshiped in the Wakan Wacipi or Grand Medicine Ceremony (Skinner 1920:273).

This hill belongs to a class of sacred lodges (hills) where the spirits meet to decide the help, if any, they will grant humans. Prehistorically the waters of the lake flowed up to the east side of this hill, to the door or entrance of this the Water Spirit’s home. The spirits could enter and exit their home to do their business within this sacred lake. Unfortunately the entrance to this sacred hill was blown closed with dynamite in the 1930’s when a local rancher discovered a den of coyotes living within. If one looks closely at the change in vegetation, the location of the former entrance can be discovered.

There are many heart hills or buttes in the state but this most important one is at Spirit Lake. Examples of other heart hills are: The Heart of the Turtle Mountain or as it is known today Butte Saint Paul. It is located in Cordella Township (13-162-74) Bottineau County. There is also a Heart Butte located on the Ft. Berthold Reservation (9-148-92) in northeastern Dunn County. Cavalier County has a Heart Butte (19-162-62), as well as Grant County (23-137-89).

Thomas F. Eastgate records in his notes two northerly connected hills who he calls ‘sisters’ to Heart Hill (Eastgate). This must be a non-Indian name or a mistranslation as features on the earth are considered male. As an example there is a Sanborn Hill or “Heart Hill’s Little Brother” located in Heman Township (1-139-59) Barnes County named for its exact appearance but smaller stature than the hill presently under discussion.

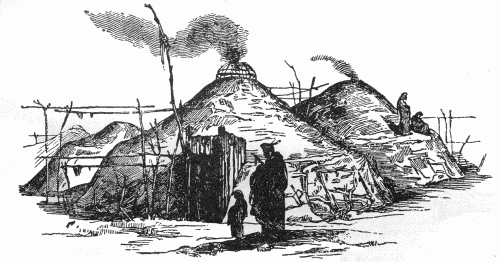

The Spirit Lake area formerly belonged to the Hidatsa. Their main earthlodge village was located on the west end of Graham’s Island, now a peninsula jutting into northwestern Spirit Lake (Devils Lake). The Hidatsa name for Heart Hill is Mirixopa Nata Sh or Heart of the Holy Water. Hidatsa traditions acknowledge the tribe was ‘born’ at Heart Hill. In a narrative similar to the European tale of Jack and the Bean Stalk, the tribe emerged from an underworld by climbing a vine. Unfortunately the vine broke leaving half of the people in their subterranean world. The Hidatsa departed the Spirit Lake area circa 1550 when their leader was told in a dream to move west to the Missouri River (Bowers 1992:22; Milligan 1972; Libby Papers Box 29: folder 14; Kittleson 1992:15).

The Hidatsa have many Lake Region legends and tales, especially about geophysical features. One story that is remembered, tells of them making a stone effigy of a bear on the north side of Heart Hill. A bison effigy is mentioned too. Dana Wright was shown a trail of 385 stones leading 450 feet to the west from the hill (Roy Johnson Papers).

In 1839 Nicollet visited the area to map the lake and surrounding area. He drew a sketch map from the top of the hill. Today one can see the same view of Black Tiger Bay just as it was drawn some 166 years ago because little has changed (Bray and Bray 1976:192).

I have a reference to this hill in 1855 bring called Clarence Peak.

Dr. Charles Eastman writes in his book Indian Boyhood of visiting Heart Hill in the 1860’s and was informed a great medicine man named Cotanka (Reed or Flute) was buried on top (Eastman 1971:163). A man by the name of Charles Belgarde is also buried on top of the hill (St. Ann’s Centennial). In June of 1992 a group of Crow Indians from Montana ascended the hill and erected two shades for the purpose of a vision quest. A four post shade was erected on the top at the west end, and another on the east end. A year later local children began to dig in the abandoned post holes and discovered a skull and arm bones. The bones were eventually sent to the State Historical Society of North Dakota in Bismarck for evaluation (Devils Lake Journal).

Father Genin on March 4, 1868 erected a thirty three foot tin laminated oak crucifix, but it was destroyed by a prairie fire, or a wind storm. On July 22, 1873 another cross of glass and steel construction replaced the wooden cross (Cory-Forbes Papers: Box 2; Norton 1931:163). Both crosses were said to be spectacular when they reflected the suns rays. Some say that glass particles can still be found at the base of the hill, remnants of the second cross. Father Genin (Richard 1975:3) renamed the hill The Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, a name closer to the original intent of the Indians. It is better than the present non-Indian name of Devils Heart (Cory-Forbes Papers: Box 2).

I was told that in1924, on a day with a clear blue sky a local church group went to Heart Hill for a picnic. They sang a hymn and the minister said a prayer, a single white cloud approached and poured hail and lighting upon them, sending them for cover. From a religious aspect one could say the Thunders were attacking the Water Spirits lodge.

Heart Hill has been used for recreational purposes during the last century. There is a photograph of a ski jump built upon the top of the hill. It has been a favorite hiking destination as well as winter sledding, especially for local school classes. By the 1930’s the ski jump was moved to a location by Highway 57 where its skeleton can be seen today. Yearly a wagon train camps for one night at the base of the hill. It is a favorite site to take visitors who have the stamina to climb to the top.

Most if not all you readers would naturally assume the Spirit Lake Tribe owns this sacred hill. You would of course be wrong. When the Spirit Lake Reservation land was allotted to individuals in accordance with the Treaty of 1872-73 and Dawes Act of 1887, no tribal member selected the hill. The ownership of land was against Indian thought. How could anyone think of owning a sacred location? No one can own land, it belongs to God. When the reservation was opened to non-Indian ownership in 1904, the hill was selected by a Whiteman and remains so today. However if we analyze the situation, this non-Indian really doesn’t own Heart Hill, all he has to do it not pay his taxes for five years.

Bibliography

Bowers, Alfred W. Hidatsa Social and Ceremonial Organizations.

University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London 1992.

Bray Edmund C. Joseph N. Nicollet on the Plains and Prairies: Expeditions

Bray, Martha Coleman of 1838 39 with Journals, Letter, and Notes on the Dakota

Translators and editors Indians. Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul; 1976.

Centennial Committee St. Ann’s Centennial, 100 years of Faith 1885 – 1985

Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation, Belcourt, ND

Cory – Forbes Papers (1853 -1927) A-C833 Box 2, Minnesota Historical Society,

St. Paul. Three boxes and 10 volumes.

(Father Genin and the crosses)

Devils Lake Journal “B.I.A. Probes Bone Discovery” May 19, 1993.

Eastgate, Thomas F. Papers. (1855-1907) Location unknown.

Formerly located in Larimore, ND.

Withdrawn by family possibly to Minot, ND.

Eastman, Charles A. Indian Boyhood.

Dover Publications, Inc. New York. 1971.

Eastman, Charles A. “The Wars of Wakeeyan and Unktayhee”

Eastman, Elaine Goodale Wigwam Evenings: Sioux Folk Tales Retold

University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln 1990. Pp. 117 – 121.

Hanson, Jeffrey R. “Ethnohistoric Problems in the Crow – Hidatsa

Separation”

Archaeology in Montana 20 (3) Pp. 7-85. Billings 1979

Kittleson, Cindy Cooper “Legends and Lore in Devils Lake”

Going Places 2 (9) September 1992 Pp 14 &15.

Libby, Orin Grant Papers A85 State Historical Society of North Dakota, Bismarck.

Matthews, Washington Grammar and Dictionary of the Language of the Hidatsa:

Introductory Sketch of the Tribe.

Cramoisy Press, New York. 1873.

Mattison, Ray H. “Report on the Historic Sites in the Garrison Reservoir

Area, Missouri River”.

North Dakota History 22 (1&2) 1955

Milligan, Edward A. The Indian in the Northern Plains.

North Dakota State University – Bottineau, 1972

No page numbers, probably written for his classes.

Norton, Sister Mary “Catholic Missions and Missionaries”

Aquinas O.S.F. North Dakota Historical Quarterly 5 (3) April 1975

Richard, Frank “St. Benedict of Wild Rice”

Red River Valley Historian Summer 1975.

Skinner, Alanson “Wahpeton Dakota Wakan Wacipi or Medicine Dance”

Indian Notes and Monographs 4, 1920 Pp. 262-340.

Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation.

New York, NY.

Glossary

Backbone Miniwakan Cankahu (Mini = water; Wakan = sacred, holy; Canka

= back; Hu = bone). A continuous ridge on the south side of Spirit Lake beginning at Sully’s Hill, travels east to the St. Michael area and then swings south to end at the Sheyenne River.

Black Tiger Bay Located on the south shore of Spirit Lake north of Tokio, ND

Named for Igmusapa (Black Panther) DLS #482 1829 – 1915.

Butte de Couer French: Heart Hill (Butte = hill; de = of the; Couer = heart).

Butte St. Paul Heyatanka Cante Paha (He = mountain; Yatanka = great; Cante =

heart; Paha = hill). Heart Hill at the Great Mountain (Turtle Mountain) has an elevation of 2305 above sea level.

Cotanka Medicine man buried on top of Heart Hill. His name translates

Reed, also whistle or flute as reeds were used for this purpose.

Eastman, Charles A. Ohiyesa (Ohiya = to win; Sa= continually) an Eastern Dakota

who fled to Canada via Spirit Lake as a boy. He later became a

medical doctor.

Genin, Father Jean-Baptiste Genin an Oblate missionary was born in France 1837. Immigrated to Canada in 1860, in 1865 he journeyed to St. Boniface (Winnipeg, Manitoba), May 7, 1865 went to Ft. Abercrombie which later became his headquarters. He didn’t get along with the settlers because as soon as he selected land for an Indian mission squatters would take the land. The administering to Indians became a bone of contention with Bishop Shanley of Fargo, a new comer who wanted Genin to establish non-Indian churches. He did establish churches at White Earth, Detroit Lakes,

and Moorhead, MN. He died at Bathgate, ND; January 18, 1900

(Richard 1975).

Graham’s Island Named for Duncan Graham, a Scottish fur trader who operated a post on the island circa 1815. His Indian name was Hoarse Voice

(Hoġita) probably named for his brogue.

Heart Hill Miniwakan Cante Paha (MiniWakan = sacred water; Cante = heart;

Paha = hill), located in the Northwest quarter of the northwest quarter of Section four, Woodlake Township, Benson County.

Hidatsa The Red Willow People, meaning they were tall and slender as the

Red Willow. They gathered at the mouth of the Knife River where

it enters the Missouri River near present Stanton, ND (Mercer County) is today in three villages. The River Crow separated from the Big Hidatsa Village (Midahati Sh = Willow Village) and the Mountain Crow separated from Sakakawia Village (Awatixa Sh = Elongated Village) (Mattison 1955:22-23; Hanson 1979).

Kame Sand and gravel deposited by the melting glacial ice. A hole in the

ice sheet would be filled with sand and gravel. When the ice sheet

melted, the result was a hill. Geologists use the term kame.

Mirixopa Nata Sh Hidatsa for Heart Hill (Miri = water; Xopa = holy, sacred; Nata =

Heart; Sh = definite article [the] used for personal names and places) (Matthews1873).

Sanborn Hill Miniwakan Cante Paha Sunkaku (Miniwakan = Sacred Water [Spirit Lake]; Cante = heart; Paha = hill; Sunkaku = his younger

Brother) The younger brother of the Heart Hill at Spirit Lake.

Unktehi Water Spirit (Un = to be; K = inserted for euphony; Teĥike = terrible, difficult). The Difficult (to deal with) One. The Water

Spirits are the meniscus of the Thunders. Their battles explain the hydrological cycle (Eastman and Eastman 1990).

Wright, Dana He was the premier historian for the state of North Dakota.

His primary interest was military trails, publishing his findings

in North Dakota History in the 1950’s.