The Remains Of Killdeer Mountain

Industry Encroaches On Historical Landmark

By Dakota Wind

Killdeer, N.D.– A Lakota tradition is that blue is a sacred color, all colors are, but blue is special. It’s the color of heaven. It’s the color of Iŋyaŋ’s (Stone's, or Rock's) sacrifice and of life that came forth in the Lakota creation story.

Aŋpó, the sun, stepped above the far horizon and golden light poured into the Mnišoše (Water-Astir; Missouri River) valley. The sky was clear and clean. Not a cloud in heaven dare bar the sun today. An uncle of mine likened days like these to be very special. ”Waŋžila tȟó,” I heard him breathe out after a long yawn of air, “It means complete blueness or blue oneness.”

A quiet wind kissed me on the face and through my hair on the way to my car. A wave of melancholy took me momentarily as I remembered my uŋči(grandmother) on mornings like this. She’d rise when the sun was just a promise of light on the lip of the world and down a tall glass of water and pray in-between deep draughts, then she’d ready herself for a walk along the river.

The drive to Killdeer was pleasant. I carpooled with friends and we exchanged pleasant conversation on the drive west. Both are archeologists and shared stories about work in the field. Conversation made the trip short and soon enough we were in the rumbling city of Killdeer.

We stopped at the city park where a motley collection of local landowners, historians, more archaeologists, a biologist, and members of various organizations had gathered in fellowship to see Killdeer Mountain before more industrial development lay claim to the earth.

I am reminded of an interpretation of eucharist after a round in introductions. It’s a religious term generally held to mean the part of a Christian service in which the Gifts are brought forward, the Thanksgiving. One of my university professors, a Benedictine sister, in class one day said that, too, when people come together for a common purpose, at a common time, and at a common place, that it is eucharist.

The introductions in and of itself, was held in a circle. There might not have been prayer, but I felt something mutual pass among everyone who was there.

A few local landowners, the Jepsons and the Sands, hosted a picnic on the rise of the west side of Killdeer Mountain. The modest spot of land was an old tipi encampment site. Tertiary flint flakes lay scattered about on unturned soil. Native grasses, medium or middle grasses, grew unhindered about the gentle rise. The gentle wind combed its breeze through the grass, the trees shushed the landscape, and thousands of native flowers crowned the hill in yellow, purple, blue, pink, and white.

Ancient cracked and worried stone testified to archaeologists that the steppe was once under a vast freshwater ocean millions of years ago. Old shattered stone broke the soil in defiance of the wind and rain. The formations looked deceptively small from a distance. Either I shrank as I approached the stones or they grew with each step.

In the days of legend, the Mandan said that the son of Foolish Boy was killed at the plateau by the spirits who dwelt there. Foolish boy retaliated by taking up his staff and struck the plateau, cleaving the plateau as we see it today. The Mandan know the mountain by another name, Singing Butte.

I embraced the illusion of the changing hillside and hiked up to the western most point of the Killdeer plateau. Deer lived there. Careless prances quickly turned to startled runs at the arrival of people. They were sunning themselves only moments earlier in the grassy rise as evidenced by depressions in the grass. A few ground plums were nibbled on and abandoned, but there were a few more near the top.

Looking north, here's one of the ravines which leaves the west side of Killdeer and goes west to Elk River (Little Missouri River).

From the top of the western most rise of Killdeer Mountain I saw two ravines stretching west through the cracked thirsty earth to Heȟáka WakpáMakȟočhe (Elk River Country; the Little Missouri River). There, in 1864, after Sully’s assault on Sitting Bull’s Huŋkpapȟa camp on the southeastern rise of Killdeer Mountain, he ordered his soldiers to pursue the Lakȟóta into the Badlands.

The Lakȟóta had been at Killdeer Mountain for a few reasons, but the most important to the people was that it was a place to hunt. In Lakȟóta, they call the plateau Tȟáȟča Wakhúte, The Place Where They Kill Deer. In July, they were hunting and gathering some of the very foods I saw on my hike. Kȟáŋta (wild plums), maštíŋčaphuté (buffalo berries), čhaŋpȟáhu (chokecherry bushes), ptetȟáwote (ground plums) all upon the hillside in abundance.

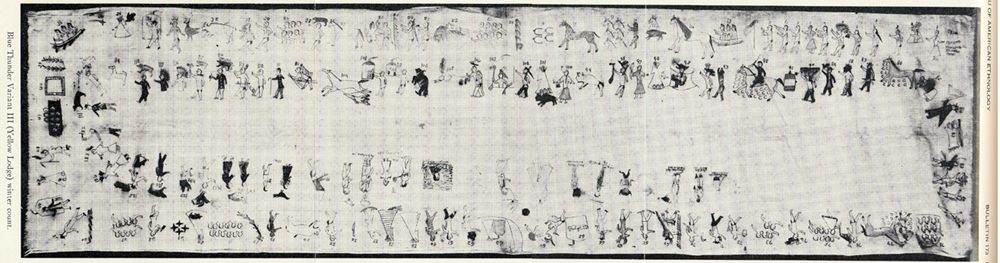

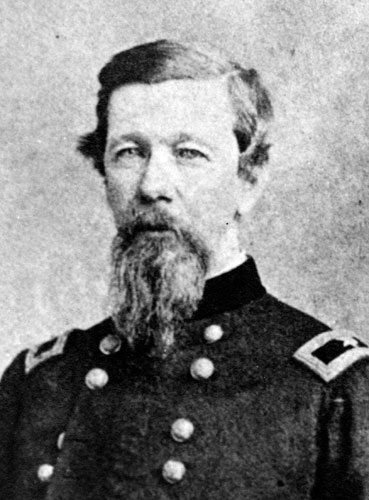

General Sully was there to level the might of the U.S. military upon the Sioux in a punitive campaign for the Eastern Dakota’s participation in the 1862 Minnesota Dakota Conflict. Aside from obliteration of homes, the deaths of as many as 300, about 150 prisoners, and destruction of foodstuff for the coming winter, Sully’s aggressive campaign succeeded in shaping the opinion of the Huŋkpapȟa and other Lakȟóta tribes throughout the era of western settlement. Warfare between traders, land surveyors, the railroad, settlers, and the Lakȟóta continued throughout the 1860s and 1880s.

I descended the western point of Killdeer Mountain enjoying the sun that warmed me and the breeze that cooled me. The hikers I was made a circuit of our ascension and descended on a ridgeline back to the old encampment site. There, the contentment of edification and gratification washed away from me at the site of two oil stakes. Did I miss them somehow while the picnic was happening earlier? Did I look past the stakes? Did I preoccupy myself with the setting of old encampment site? I must have, and a dreadful feeling of fatalism filled me.

Industry will be here soon. The earth will be turned, a well pad and a road will go in, and physical memory of a Lakȟóta camp will vanish entirely.

Mr. Rob Sand and Ms. Lori Jepson reflected about the experience of preserving Killdeer Mountain.

Two local landowners expressed their heartfelt wishes that they could have done more. When the oil companies came to gauge the earth for mineral extraction, they weighed the hearts and minds of an otherwise close-knit community. Some individual land owners were lured by the promise of an income far more than what the humble rancher earns through his sweat.

Rob Sand, one of the local landowners, was asked by a visitor from out of state if there was any one thing he could change, and without a moment’s hesitation, Sand simply replied, “I would change the minds of the Industrial Commission.” Sand, a common man who holds the land dear as his settler ancestors and who finds beauty in the untouched and unturned land, carefully articulated - but not once criticized the character of the men who make up the North Dakota Industrial Commission nor the Director of the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources - his deepest desire to preserve the history and heritage of the Killdeer Mountain.

The oil under the Killdeer plateau isn’t much, somewhere between three and three and a half million barrels of oil, but its enough that it’s considered a waste if its left there. That’s enough oil to power to the United States for over four hours, if it’s going to the U.S.

A golden eagle flew straight out of a nest near the top of Killdeer Mountain.

A visit to the Killdeer Mountain conflict site is capped by the regal nature of the eagles’ aeries on a south facing cliff side of Killdeer Mountain. Golden eagles ride the endless prairie wind, a wind that has been constant since before the landscape was under the ocean, before Foolish Boy cracked the plateau.

Jagged cracked stone reaches out from Killdeer Mountain.

The climb up the mountain to the summit to where Medicine Hole sings is filled with pauses to enjoy the view by some. I look at the degree of ascension, anywhere from a 30° incline at the base to 90° on the cliff side. I imagine women holding babies and shepherding children in an escape from Sully’s command and thanked God I’m here today.

Indian Paint. My pictures of this flower did not turn out. Here is an image from Wikimedia Commons.

Orange lichen clings to shattered stone. A forest of stunted white birch grows on the south face about half-way to the flat summit. More native flowers, purple, grow delicately in the cracks and crevices. Some Lakȟóta smile and call it “love medicine.” I recognize one yellow flower that some call “Indian Paint,” that one could acquire yellow or purple pigment.

Along the way, a work crew had placed seismic sensors to measure the impact of oil wells a half-mile away, which makes me conscience of the well flares and further away, constant truck traffic on the roads. Men would ascend the plateau to remove their selves from the noise and distraction of everyday camp life. In seclusion, they prayed under a searing sun, they prayed in the winds, they prayed in moonlight and starlight. People still go to pray on Killdeer Mountain.

A traditional pilgrim created a medicine wheel from the broken white stone about the summit. I left a handful of seeds before I descended. The evening was as cloudless as the morning, sunlight golden again in the evening, the same breeze or perhaps a different one entirely, kissed my brow as I stepped into Killdeer’s shadow.

By day the air is drawn into Medicine Hole, at night it is exhaled like breath. The wind isn't seen by the dust of the earth that comes out, it is hear, and what is heard is the song of Makȟočhe, of Grandmother Earth.

.jpg)

.jpg)